Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami, Burning Country – Syrians in Revolution and War.

London, Pluto Press, 2016, 262pp.

Although this overview of Syrian society was written before the January 2025 flight of Bashar al-Assad to Moscow and the coming to power of Ahmed al-Sharaa as “interim” President, the book is a useful guide to many of the current issues in Syria today.

As Khalil Gibran wrote in The Garden of the Prophet, thinking of his home country, Lebanon, but it can also be said of the neighboring Syria, “Pity the nation divided into fragments, each fragment deeming itself a nation.” The fragments, ethnic and religious to which are added deep social divisions, make common action difficult. The Druze, the Alaouites, the Kurds, all play an important role but are often fearful of each other. Some of the Alaouites have fled to Lebanon. At the same time, there is a slow return of Syrians who have been in exile in Turkey and western Europe – especially Germany.

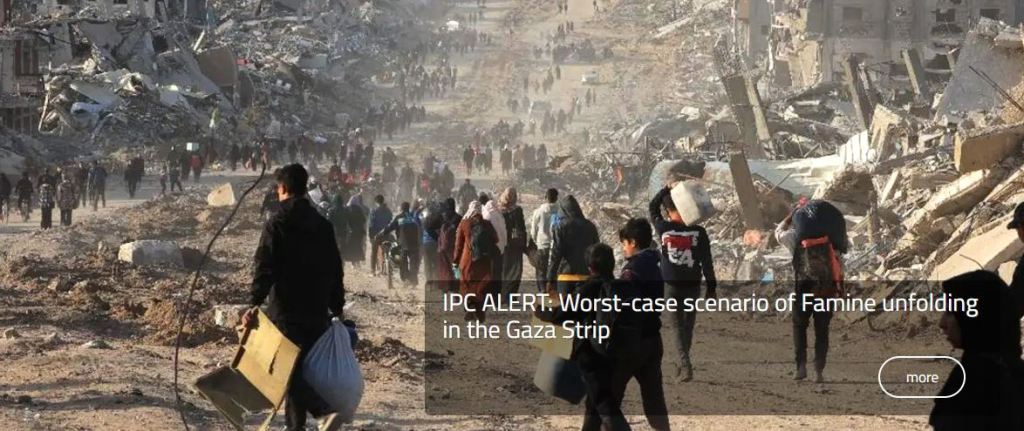

The divisions were made deeper by the years of violent conflict against the government of Bashar al-Assad which began in March 2011 with youth-led demonstrations appealing for a Syrian republic based on equality of citizenship, the rule of law, respect for human rights, and political pluralism.

After some months of non-violent protests, members of the military deserted, taking their weapons with them. The Syrian conflict became militarized. A host of armed militias were formed, often hostile to each other.

From late 2013 to February 2014, there were negotiations for a ceasefire held at the United Nations (UN), Geneva. Representatives of the Association of World Citizens (AWC) met with the Ambassador to the UN of Syria, as well as with the representatives of different Syrian factions who had come to Geneva. Unfortunately, Syrian politics has been that of “winner takes all” with little spirit of compromise or agreed-upon steps for the public good. The AWC called for a broad coming together of individuals who believe in non-violence, equality of women and men, ecologically-sound development, and cooperative action for the common good. The need to work together for an orderly creation of the government and the development of a just and pluralistic Syrian society is still with us.

Robin Yassin-Kassab’s book is a useful guide to the forces that must come together and cooperate today.

Prof. René Wadlow is President of the Association of World Citizens.