Par Bernard J. Henry

Il fallait s’y attendre. Après la mort de l’Afro-Américain George Floyd à Minneapolis (Minnesota) le 25 mai, étouffé par le policier Derek Chauvin et ses collègues auxquels il criait du peu de voix qu’ils lui laissaient « I can’t breathe », « Je ne peux pas respirer », et avec la vague mondiale d’indignation que le drame a soulevée quant au racisme et aux violences policières, l’Afrique s’est élevée d’une seule voix à l’ONU.

Le 12 juin, les cinquante-quatre pays du Groupe africain de l’Assemblée générale des Nations Unies ont appelé le Conseil des Droits de l’Homme à un « débat urgent sur les violations actuelles des droits de l’homme d’inspiration raciale, le racisme systémique, la brutalité policière contre les personnes d’ascendance africaine et la violence contre les manifestations pacifiques ».

Avec les cinquante-quatre pays africains, c’étaient plus de six cents organisations non-gouvernementales, dont l’Association of World Citizens (AWC), qui appelaient le Conseil à se saisir de la question. Et le 15 juin, la demande a été acceptée sans qu’aucun des quarante-sept Etats qui composent le Conseil ne s’y soit opposé. Le débat demandé a donc eu lieu, sur fond de dénonciation d’un « racisme systémique » par Michelle Bachelet, Haute Commissaire des Nations Unies pour les Droits de l’Homme, mais aussi d’indignation des cadres onusiens originaires d’Afrique contre leur propre institution qu’ils jugent trop passive.

Une fresque en hommage à George Floyd sur un mur de Chicago (Illinois).

Pour l’Organisation mondiale, il s’agit plus que jamais de n’entendre pas seulement la voix de ses Etats membres, mais aussi celle du peuple du monde qui s’exprime en bravant les frontières, parfois même ses dirigeants. La mort de George Floyd et l’affirmation, plus forte que jamais, que « Black Lives Matter », « Les vies noires comptent », imposent une responsabilité historique à l’ONU qui, en matière de racisme, n’a plus droit aux rendez-vous manqués, réels et présents dans son histoire.

Résolution 3379 : quand l’Assemblée générale s’est trompée de colère

Le 10 novembre 1975, l’Assemblée générale de l’ONU adoptait sa Résolution 3379 portant « Élimination de toutes les formes de discrimination raciale ». Malgré ce titre prometteur, le vote de l’Assemblée générale cristallisait en fait les frustrations des Etats Membres quant à deux situations de conflit, jugées les plus graves au monde depuis la fin de la guerre du Vietnam en avril – l’Afrique australe et le Proche-Orient.

A côté de l’Afrique du Sud ou règne l’apartheid, la ségrégation raciale érigée en système par la minorité blanche aux dépens de la population noire autochtone, se tient l’ancêtre de l’actuel Zimbabwe, la Rhodésie, Etat proclamé en 1970 sur une colonie britannique mais non reconnu par la communauté internationale. La Rhodésie n’est pas un Etat d’apartheid proprement dit, mais sa minorité blanche tient la majorité noire sous la chappe brutale d’un paternalisme colonialiste. Deux organisations indépendantistes, la ZANU et la ZAPU, s’y affrontent dans une violente guerre civile et le gouvernement principalement blanc de Ian Smith n’y veut rien entendre.

Dans l’Afrique du Sud de l’apartheid, même sans le dire, une plage réservée aux Blancs était interdite aux Noirs au même titre qu’elle l’était aux chiens.

Au Proche-Orient, la création en 1948 de l’Etat d’Israël s’est faite sans celle d’un Etat palestinien que prévoyait pourtant le plan original de l’ONU. En 1967, lors de la Guerre des Six Jours qui l’oppose aux armées de plusieurs pays arabes, l’Etat hébreu étend son occupation sur plus de territoires que jamais auparavant, prenant le Sinaï à l’Egypte – qui lui sera rendu en 1982 – et le Golan à la Syrie, la Cisjordanie et Jérusalem-Est échappant quant à elles à la Jordanie. Aux yeux du monde, l’idéal sioniste des fondateurs d’Israël signifie désormais principalement l’oppression de la Palestine.

Et les deux Etats parias de leurs régions respectives avaient fini par s’entendre, causant la fureur tant de l’URSS et de ses alliés à travers le monde que du Mouvement des Non-Alignés au sud. Le 14 décembre 1973, dans sa Résolution 3151 G (XXVIII), l’Assemblée générale avait déjà « condamné en particulier l’alliance impie entre le racisme sud africain et le sionisme ». C’est ainsi que deux ans plus tard, la Résolution 3379 enfonçait le clou contre le seul Israël en se concluant sur ces termes : « [L’Assemblée générale] [c]onsidère que le sionisme est une forme de racisme et de discrimination raciale ».

Impossible de ne pas condamner l’occupation israélienne en Palestine, tant elle paraissait incompatible avec le droit international qui, en 1948, avait précisément permis la création de l’Etat d’Israël. Pour autant, assimiler le sionisme au racisme présentait un double écueil. D’abord, s’il se trouvait un jour une possibilité quelconque d’amener Israéliens et Palestiniens au dialogue, comment Israël allait-il jamais accepter de venir à la table des négociations avec un tel anathème international sur son nom ? C’est ce qui amena, après la Première Guerre du Golfe, l’adoption par l’Assemblée générale de l’ONU de la Résolution 46/86 du 16 décembre 1991 par laquelle la Résolution 3379, et avec elle l’assimilation du sionisme au racisme, étaient tout simplement abrogées, ce qui était l’une des conditions d’Israël pour sa participation à la Conférence de Madrid en octobre. Ensuite, plus durablement cette fois, présenter l’affirmation d’un peuple de son droit à fonder son propre Etat comme étant du racisme ne pouvait qu’alimenter le refus, ailleurs à travers le monde, du droit à l’autodétermination déjà mis à mal dans les années 1960 au Katanga et au Biafra, avec à la clé, l’idée que toute autodétermination allait entraîner l’oppression du voisin.

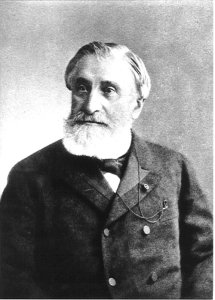

« Les racistes sont des gens qui se trompent de colère », disait Léopold Sédar Senghor. Il n’en fut pire illustration que la Résolution 3379, inefficace contre le racisme et n’ayant servi qu’à permettre à Israël de se poser en victime là où son occupation des Territoires palestiniens n’avait, et n’a jamais eu, rien de défendable.

Un échec complet donc pour l’ONU, mais qui fut réparé lorsque commença le tout premier processus de paix au Proche-Orient qui entraîna, en 1993, les Accords d’Oslo et, l’année suivante, le traité de paix entre Israël et la Jordanie. C’était toutefois moins une guérison qu’une simple rémission.

Durban 2001 : l’antiracisme otage de l’antisémitisme

Le 2 septembre 2001 s’est ouverte à Durban, en Afrique du Sud, la Conférence mondiale contre le racisme, la discrimination raciale, la xénophobie et l’intolérance, conférence organisée par les Nations Unies. Sans même évoquer la Résolution 3379 en soi, depuis son abrogation en 1991, le monde avait changé. La Guerre Froide était terminée, l’URSS avait disparu, l’apartheid avait pris fin dans une Afrique du Sud rebâtie en démocratie multiraciale par Nelson Mandela auquel succédait désormais son ancien Vice-président Thabo Mbeki.

Au Proche-Orient, Yitzhak Rabin avait été assassiné en 1995, et avec lui étaient morts les Accords d’Oslo réfutés par son opposition de droite, cette même opposition qui dirigeait désormais Israël en la personne d’Ariel Sharon, ancien général, chef de file des faucons et dont le nom restait associé aux massacres de Sabra et Chatila en septembre 1982 au Liban. Aux Etats-Unis, le libéralisme international des années Clinton avait fait place aux néoconservateurs de l’Administration George W. Bush, hostiles à l’ONU là où leurs devanciers démocrates avaient su s’accommoder du Secrétaire général Kofi Annan. Le monde avait changé, mais c’était parfois seulement pour remplacer certains dangers par d’autres. Et le passé n’allait pas tarder à se rappeler au bon souvenir, trop bon pour certains, des participants.

La Haute Commissaire des Nations Unies pour les Droits de l’Homme, Mary Robinson, n’était pas parvenue à mener des travaux préparatoires constructifs, et dès le début des discussions, le résultat s’en est fait sentir. Devant la répression israélienne de la Seconde Intifada à partir de fin septembre 2000, l’Etat hébreu déclenche une fois de plus la colère à travers le monde. Un nombre non négligeable d’Etats rêvent de déterrer la Résolution 3379, mais cette fois, sans plus de racisme sud-africain auquel accoler le sionisme, Israël va voir cette colère dégénérer en récusation non plus du sionisme mais, tout simplement, du peuple juif où qu’il vive dans le monde.

A gauche, Ariel Sharon, alors officier supérieur de Tsahal, en 1967. Plus tard Ministre de la Défense puis Premier Ministre, son nom sera associé à de graves crimes contre les Palestiniens commis par Israël.

S’y attendant, l’Administration Bush a lancé des mises en garde avant le début de la conférence. En ouverture, Kofi Annan annonce la couleur – il ne sera pas question de sionisme, pas de redite de 1975. Rien n’y fait. Toute la journée, des Juifs présents à la conférence sont insultés et menacés de violences. Le Protocole des Sages de Sion, faux document né dans la Russie tsariste au début du vingtième siècle pour inspirer la haine des Juifs, est vendu en marge. Et, comble pour une conférence des Nations Unies, même si elles n’y sont bien entendu pour rien, il est distribué aux participants des tracts à l’effigie, et à la gloire, d’Adolf Hitler.

Il n’en faut pas plus pour qu’Etats-Unis et Israël plient bagages dès le lendemain. Si la France et l’Union européenne restent, ce n’est cependant pas sans un avertissement clair – toute poursuite de la stigmatisation antisémite verra également leur départ.

C’est à la peine qu’est adopté un document final, dont ce n’est qu’en un lointain 58ème point qu’il est rappelé que « l’Holocauste ne doit jamais être oublié ». Dans le même temps, un Forum des ONG concomitant adopte une déclaration si violente contre Israël que même des organisations majeures de Droits Humains telles qu’Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch et la Fédération internationale des Ligues des Droits de l’Homme s’en désolidarisent. Le Français Rony Brauman, ancien Président de Médecins Sans Frontières, ardent défenseur de la cause palestinienne, n’avait pu lui aussi que déplorer l’échec consommé de la conférence, prise en otage par des gens qui prétendaient combattre le racisme, y compris, naturellement, le colonialisme israélien, mais n’avaient en réalité pour but que de répandre le poison de l’antisémitisme.

Pour la dignité de chaque être humain

Le racisme est un phénomène universel, qui n’épargne aucun continent, aucune culture, aucune communauté religieuse. De la part de l’ONU, c’est en tant que tel que le peuple du monde s’attend à le voir combattu. Par deux fois, les Etats membres de l’Organisation mondiale l’ont détournée de sa fonction pour plaquer le racisme sur ce qui était, et qui demeure, une atteinte à la paix et la sécurité internationales, nommément l’occupation israélienne en Palestine où, indéniablement, le racisme joue aussi un rôle, mais qui ne peut se résumer à la seule question de la haine raciale comme c’était le cas de l’apartheid en Afrique du Sud ou comme c’est aujourd’hui celui du scandale George Floyd.

Ici à New York en 2014, le slogan “Black Lives Matter”, qui exprime désormais le droit de tout être humain opprimé en raison de son origine au respect et à la justice.

S’il ne peut ni ne doit exister d’indulgence envers quelque Etat que ce soit, en ce compris l’Etat d’Israël, le racisme sous toutes ses formes, surtout lorsqu’il provient d’agents de l’Etat tels que les policiers, ne peut être circonscrit à la condamnation d’une seule situation dans le monde, aussi grave soit-elle, encore moins donner lieu à l’antisémitisme qui est lui aussi une forme de racisme et l’on ne peut en tout bon sens louer ce que l’on condamne !

Par bonheur, le Groupe africain a su éviter tous les écueils du passé, ayant lancé un appel au débat qui fut accepté sans mal par le Conseil des Droits de l’Homme. Les appels de la Haute Commissaire aux Droits de l’Homme et des hauts fonctionnaires d’origine africaine viennent amplifier un appel que l’ONU doit entendre. Le monde s’est réveillé, il faut en finir avec le racisme, et sur son aptitude à agir, à accueillir les critiques, l’ONU joue sa crédibilité dans cette lutte pour la dignité de chaque être humain qui est le premier des droits.

Bernard J. Henry est Officier des Relations Extérieures de l’Association of World Citizens.