Par Bernard J. Henry

Voilà un mois tout juste, le 10 décembre dernier, la Déclaration universelle des Droits de l’Homme (DUDH) avait soixante-quinze ans. Pour le mouvement Citoyen du Monde, son adoption au Palais de Chaillot à Paris, qui accueillait cette année-là l’Assemblée générale de l’ONU, va de pair avec la venue de Garry Davis en France pour y renoncer à sa nationalité américaine puis tenter de venir camper sur le «territoire international» de l’ONU et, enfin, interrompre l’Assemblée générale avec Robert Sarrazac pour y exiger un gouvernement mondial et une assemblée des peuples. A l’autre bout du monde se créait la Société californienne des Citoyens du Monde d’où sortirait, en 1974, l’Association of World Citizens (AWC).

Un anniversaire, donc, mais pas une fête. Le pogrom antisémite du Hamas le 7 octobre dernier en Israël, la riposte entièrement démesurée du même Israël contre la population civile tout entière à Gaza, la répression toujours plus forte du régime de Vladimir Poutine en Russie à laquelle s’ajoute une campagne militaire déchaînée contre les civils dans son invasion de l’Ukraine, ainsi que les succès politiques en Europe, en Argentine et ailleurs de l’extrême droite, offrent à la vénérable doyenne du droit international des Droits Humains le bien triste cadeau de son oubli, du moins lorsqu’il s’agit de gouverner.

La veille, toutefois, avait déjà eu lieu un autre anniversaire, hélas passé inaperçu, celui d’une «proche parente» de la DUDH. Étaient-ce les soixante-quinze ans de la Convention pour la Prévention et la Répression du Crime de Génocide, adoptée le 9 décembre 1948 dans les mêmes murs du Palais de Chaillot ? C’est vrai aussi. Aînée d’un jour de la DUDH, la Convention a le mérite d’avoir su faire parler d’elle, jusqu’à aujourd’hui où, au milieu des accusations croissantes de «génocide» portées par la société civile palestinienne et internationale contre Israël au sujet de Gaza, d’aucuns se voient bien l’invoquer pour incriminer l’État hébreu devant les juridictions internationales. La «proche parente» dont l’anniversaire, qu’elle partage avec la Convention, a été oublié ou presque est autrement plus jeune, tout aussi essentielle à la société civile internationale que méconnue du grand public.

Née le 9 décembre 1998, soit un demi-siècle après la DUDH, à l’Assemblée générale des Nations Unies alors installée déjà de longue date en ses locaux attitrés de New York, elle porte un nom d’état-civil barbare : «Déclaration sur le droit et la responsabilité des individus, groupes et organes de la société de promouvoir et protéger les droits de l’homme et les libertés fondamentales universellement reconnus». Mais pour l’ONU elle-même, pour les juristes internationaux et pour les gens auxquels elle se destine, ces gens qui font partie de son nom même, elle s’appelle la Déclaration sur les Défenseurs des Droits de l’Homme (DDDH).

«Mieux vaut allumer une petite chandelle que maudire les ténèbres», affirme un proverbe chinois. Justement, en Chine, pour nombre de DDH persécutés, emprisonnés, parfois torturés par le pouvoir, qu’il s’agisse de Han, l’ethnie majoritaire à laquelle le monde résume souvent trop vite la population chinoise, ou de peuples envahis et occupés par la Chine comme les Tibétains ou les Ouïghours, la DUDH reste souvent cette dernière chandelle avant les ténèbres du désespoir sous les coups de la répression. En Chine d’où vient le proverbe, oui, «et, dans le monde, c’est partout pareil», comme le chantait Daniel Balavoine qui avait tant défendu les Droits Humains dans les textes de ses chansons.

Si la DUDH est une petite chandelle, alors, avec la DDDH, on en a deux et n’est-ce pas mieux encore ? Si, bien sûr. Et pourtant, la DDDH reste méconnue, dans l’ombre là où son illustre aînée demeure un phare même dans la pire nuit de tempête. C’est dommage. Tellement dommage, car, serait-elle tant soit peu mieux connue, la DDDH changerait bien des choses. Pour notre mouvement Citoyen du Monde, elle incarne notamment ce pour quoi les générations successives de nos militants se sont battues depuis Garry Davis – l’être humain, l’individu, libre de ses choix et responsable du bien commun au niveau du monde et de l’humanité.

La DDDH, inconnue parce qu’impuissante ?

Connaître mieux la DDDH commence par savoir déjà ce qu’elle est précisément. Une «déclaration» donc, adoptée par l’Assemblée générale de l’ONU en tant que résolution, tout comme la DUDH en son temps. Donc, un appel de pure portée symbolique et morale, et non une convention, un traité que signent et/ou ratifient des États qui, dans la théorie, rendent ainsi ses dispositions pour lui contraignantes, ces dispositions que l’État Partie s’engage à respecter et mettre en œuvre en vertu de sa propre loi. Toujours dans la théorie, la DDDH créerait donc moins d’obligations pour les États, donc moins de droits pour le citoyen, que, par exemple, la Convention européenne de Sauvegarde des Droits de l’Homme et des Libertés fondamentales (CEDH).

Pas si vite.

En Droits Humains, un texte écrit, autrement dit un instrument de «droit positif», n’a jamais suffi à créer un droit qui soit respecté dans les actes. Même les deux Pactes internationaux issus de la DUDH, relatifs pour l’un aux droits économiques, sociaux et culturels et, pour l’autre, aux droits civils et politiques, bien qu’étant des traités contraignants pour les États qui les ratifient, sont loin d’avoir jamais garanti le respect ou la mise en œuvre des droits qu’ils consacrent. A plus forte raison, de simples déclarations devraient être encore moins bien considérées et la DUDH n’aurait jamais dû être plus qu’un vœu pieux. Comment a-t-il pu en être autrement ?

Si le droit international est parfois décrié comme manquant de muscle, il faut en revanche lui reconnaître qu’il ne manque pas de tête. En l’absence de toute police ou force militaire spécialement chargée de faire respecter le droit international face aux violations les plus graves – sachant qu’un système international, centré sur la volonté politique des États, la rendrait de toute façon peu manœuvrable et que, quand bien même, sitôt cette force activée, d’aucuns auraient tôt fait de crier à la tyrannie ! – le droit international tire sa force, particulièrement en ce qui concerne les Droits Humains, de la coutume, celle qui voit les États se conformer, par leur seule volonté politique, à des règles auxquelles ils estiment devoir obéir car elles ont à leurs yeux une valeur contraignante.

Voilà pourquoi la DUDH n’est pas restée lettre morte, étant devenue tout au contraire la clé de voûte de tout le système juridique international en la matière. La DDDH, qui en est tout à la fois la cadette, l’héritière et la complémentaire, incarne ces mêmes règles de droit international qui n’ont pas au départ de caractère contraignant mais en revêtent un car les États le lui reconnaissent de leur propre initiative. La manière même dont elle a été adoptée par l’Assemblée générale de l’ONU le prouve, la DDDH étant devenue réalité non par un vote, comme l’avait fait la DUDH en 1948, mais par consensus, à savoir qu’il était tout simplement demandé aux États qui s’y opposaient de le faire savoir et aucun ne s’y est risqué. Par conviction profonde, magique de l’instant, de devoir respecter strictement ses dispositions ? Certainement beaucoup moins que par peur d’apparaître comme un État qui nie ouvertement toute importance aux DDH. C’est qu’un État, puissance souveraine ou pas, ça tient à son image …

Là où la DUDH avait été «élue» par l’Assemblée générale comme s’il s’était agi d’un parlement national, la DDDH a été «acceptée» selon une procédure quant à elle typique du droit international. Pour autant, sa nature est bien moins celle d’un instrument international que d’un texte de caractère mondial, car elle est née dans un monde lassé des nations toutes-puissantes et brûlant du désir de devenir un monde d’êtres humains.

La volonté du peuple du monde

Non, la DDDH n’est pas juste un cadeau d’anniversaire à une DUDH ayant atteint l’âge respectable de cinquante ans – respectable pour un texte de droit international, ses aïeux les traités de la Société des Nations pouvant la jalouser du fond de leurs tombes dans l’histoire du droit d’avoir eu autant de temps pour grandir. Elle est une enfant de son temps, une enfant de ces années 1990 où un monde sorti de la Guerre Froide découvrait que les atrocités de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale n’étaient pas si profondément enfouies dans l’histoire qu’il l’avait cru.

Un premier «réveil» avait eu lieu lors de la Conférence de Vienne en 1993, conférence sur les Droits Humains où le système en place jusqu’alors était apparu dans toute son inefficacité devant la purification ethnique en ex-Yougoslavie, cependant que la Somalie livrée au chaos et à la famine voyait l’opération internationale censée la secourir se transformer en une violente opération militaire contre le chef de l’une des factions de la guerre civile sur place.

Après la création du Tribunal pénal international pour l’ex-Yougoslavie le 25 mai, une première depuis les Tribunaux militaires internationaux de Nuremberg et de Tokyo, un pas important avait été franchi avec la création du poste de Haut Commissaire des Nations Unies pour les Droits Humains. Le choix du premier titulaire avait toutefois déçu, en la personne de l’ancien Ministre équatorien des Affaires Étrangères José Ayala Lasso, accusé d’avoir été jadis un acteur de la dictature militaire dans son pays.

Mais même ce faux départ ne pouvait étouffer une réalité criante, celle de la volonté du peuple du monde par-delà les langues, les religions, les cultures et les frontières politiques, celle de l’exigence d’institutions internationales qui défendent les droits de chaque être humain, ces droits nécrosés pendant tout un demi-siècle et qui, la Guerre Froide terminée, revenaient enfin à leurs titulaires et s’affirmaient même comme une criante urgence.

C’était encore sans compter sur les deux années à venir, avec le génocide du Rwanda et les massacres des forces serbes de Bosnie-Herzégovine à Srebrenica et Žepa. Dans le premier cas, un second Tribunal pénal international ad hoc allait être créé par l’ONU et, avec lui, l’idée ressurgissait du fond de son après-guerre d’un tribunal pénal international permanent et universel, évoquée après les procès de Nuremberg et Tokyo mais gelée elle aussi par cinquante ans de Guerre Froide.

C’est pourtant non sans mal que le 17 juillet 1998, à l’issue de la Conférence diplomatique de Rome, fut adopté le Statut de la Cour pénale internationale (CPI) sous réserve de sa ratification par soixante États, survenue en 2002. L’idée d’une juridiction internationale forte des Droits Humains avait plié sous le poids des réticences des gouvernements, notamment ceux des Etats-Unis et de France sur fond d’accusations d’abus commis par les troupes américaines en Somalie et françaises au Rwanda, ainsi qu’en Bosnie-Herzégovine où les Casques bleus français s’étaient vus accusés de partialité au profit de la Republika Srpska, la république serbe sécessionniste de Radovan Karadžić. A Rome même, les Etats-Unis s’étaient contentés de signer le Statut de la Cour pénale internationale sans le ratifier – signature ensuite retirée par l’Administration Bush – et la France, bien que devenue État Partie, ne s’était pas privée de dire tout le mal que lui inspirait l’idée du jugement de ses soldats par une juridiction non nationale.

L’idée restait toutefois la même : après la fin d’un demi-siècle de Guerre Froide avec, à la clé, la menace permanente d’une destruction nucléaire totale du monde, l’humanité n’accordait plus de crédit aux États pour leurs abus en matière de Droits Humains, et de ces institutions internationales censées incarner un nouvel ordre basé sur des règles universelles contraignantes, elle exigeait d’obliger les responsables de tels abus à payer cash.

Avec cette évolution juridique et judiciaire de taille, un principe se voyait consacré qui venait s’inscrire en faux contre l’idée traditionnelle du droit international depuis le temps même de la Société des Nations, le principe qui faisait de l’État le seul sujet possible dudit droit international : désormais passible de poursuites pénales devant des juridictions internationales, l’individu devenait lui aussi sujet de droit international, quoique de la pire des manières et au pire titre qui soit. Il manquait une reconnaissance de l’individu qui lui soit favorable et positive dans son esprit. Cinq mois plus tard, elle était là.

Défendre les droits sans plus avoir à choisir un camp

Même avec l’adoption de la DUDH, dont Garry Davis avait déclaré de manière bien optimiste qu’elle constituait la reconnaissance politique de l’individu sur le plan mondial, le principe de l’État comme seul sujet possible de droit international n’était pas remis en question, car la Déclaration, simple résolution de l’Assemblée générale, ne créait aucune obligation envers les États. Plus encore, les États étant les destinataires des droits dont l’individu se voyait ainsi fait titulaire, la DUDH subordonnait précisément ces droits au bon vouloir des États. Les Pactes internationaux qui en ont découlé n’ont fait que renforcer encore ce principe, même les États les plus déterminés à les respecter ayant eu la possibilité de les ratifier en émettant des réserves, autrement dit, de les ratifier «à la carte» en omettant certaines de leurs dispositions qui, peut-être, ne les arrangeaient pas.

Comment, dès lors, penser que la DDDH, elle aussi simple résolution de l’Assemblée générale et que ne vient compléter pour l’heure aucun pacte international, apporterait une reconnaissance plus réelle, a fortiori plus importante, de l’individu au niveau mondial ? Tout simplement en sortant du seul champ du droit positif pour intégrer celui de l’histoire de la notion même de DDH.

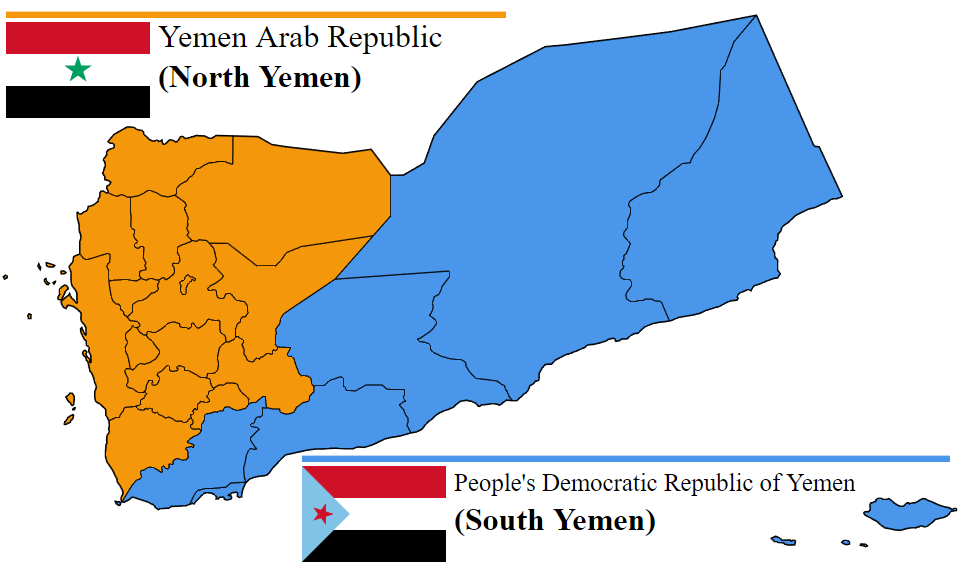

Sous la Guerre Froide, qu’était-ce donc qu’un DDH ? Bien sûr, une personne qui s’employait à la défense des droits énoncés dans la DUDH, définition première du terme. Mais dans ce contexte d’affrontement entre deux blocs par pays interposés, l’une ou l’autre des deux grandes puissances tentant d’installer ici ou là un régime allié et, pour éviter qu’il cesse un jour de l’être, dictatorial – l’un des deux grands n’ayant parfois fait qu’y remplacer l’autre, comme l’URSS à Cuba et au Nicaragua où avaient été délogés des tyrans alliés de Washington – un DDH était plus souvent perçu comme quelqu’un qui, dans un État tyrannique, défendait les droits en s’adossant au modèle proposé par celle des grandes puissances dont la tyrannie locale ne dépendait pas.

A l’Est, l’image d’Alexandre Soljenitsyne, auteur du légendaire Archipel du Goulag et exilé aux Etats-Unis où il habitait le Vermont, et à l’Ouest, celle du Chilien Pablo Neruda, homme politique communiste et surtout poète de renom, mort douze jours après le coup d’État du 11 septembre 1973 qui ouvrit la voie à la dictature militaire du Général Augusto Pinochet, officiellement d’un cancer de la prostate mais, selon d’autres sources persistantes, empoisonné par la dictature pro-américaine, trônaient dans les imaginaires des partisans d’un camp ou de l’autre, pour lesquels défendre les Droits Humains voulait dire au premier plan fustiger le camp adverse. Les critiques «internes» dans chaque camp se faisaient autrement plus rares, comme lorsque dans la France des années 1980, le Parti communiste se refusait à toute condamnation du tyran roumain Nicolae Ceausescu sur la même base que celle de la dictature de Pinochet au Chili ou quand le Front National, parti emblématique de l’extrême droite professant un anticommunisme reaganien, refusait de condamner l’apartheid en Afrique du Sud et appelait au contraire à ne pas «juger la RSA [acronyme de Republic of South Africa] selon des critères occidentaux». En ce qui concerne ce second parti, l’incohérence était telle qu’on le voyait prendre fait et cause pour les Juifs d’URSS empêchés par Moscou de rejoindre Israël alors même qu’en France, il qualifiait la Shoah de «point de détail» de l’histoire de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale …

Quoi qu’il en soit, lorsque les DDH se voyaient persécutés et qu’il fallait agir auprès de leurs gouvernements nationaux afin de les aider, il n’existait aucun texte international qui permît de mettre en avant la légitimité de leur travail, notamment pas pour les différencier de militants politiques plus classiques. De là à laisser entendre que la défense des Droits Humains était une simple option politique, pas plus défendable que celle choisie par le gouvernement qui décidait ainsi de réprimer ses DDH, il n’y avait qu’un pas, souvent très vite franchi.

En 1991, lorsque l’URSS a disparu et la Guerre Froide avec, cette iconographie du DDH défendant les victimes de l’un des deux systèmes au nom des valeurs défendues par l’autre avait fait long feu. Dès 1988, dans un monde où le Mur de Berlin était toujours debout, l’assassinat au Brésil du militant syndical et écologiste Francisco Alves Mendes Filho, dit Chico Mendes, avait mis en lumière la réalité du droit à l’environnement, non pas seulement contre les États mais aussi contre les entreprises multinationales tentées de le sacrifier pour le profit. Quatre ans plus tard, en 1992, l’an zéro de l’après-Guerre Froide, le Prix Nobel de la Paix remis à la militante guatémaltèque Rigoberta Menchú inaugurait l’image nouvelle du DDH, défendant des droits concrets, dans des contextes concrets, pour des populations concrètes, un DDH au sens réellement international du terme, traitant des questions pouvant exister partout dans le monde, un DDH avec lequel la grille de lecture jusqu’alors en vigueur perdait tout son sens. Il n’en fallait pas davantage pour que la Conférence de Vienne ne puisse que constater, l’année suivante, en 1993, que les mécanismes interétatiques de défense des Droits Humains nés sous la Guerre Froide avaient fait leur temps.

C’est dans ce contexte et au bout de ce processus d’évolution qu’a été adoptée fin 1998 la DDDH, consacrant l’individu non comme un acteur souverain et distinct des États comme le concevait Garry Davis, mais comme un acteur légitime du droit international et, à sa manière, des relations internationales qui échappaient désormais aux seules interactions entre les nations pour créer davantage un «espace mondial» selon la formule de Bertrand Badie, libéré du chantage permanent et systématique aux droits et libertés de la Guerre Froide et consacrant la défense des Droits Humains comme ce qui serait désormais le principe moteur de la vie politique mondiale. La Déclaration se montre à ce sujet sans ambiguïté puisqu’adoptée, dans les termes mêmes de son Préambule, en «[c]onsidérant les liens qui existent entre la paix et la sécurité internationales, d’une part, et la jouissance des droits de l’homme et des libertés fondamentales, d’autre part, et consciente du fait que l’absence de paix et de sécurité internationales n’excuse pas le non-respect de ces droits et libertés».

La préséance donnée à l’être humain sur l’État et, par voie de conséquence, à l’intérieur du système international lui-même est énoncée on ne peut plus clairement dans les deux premiers articles :

«Article premier

Chacun a le droit, individuellement ou en association avec d’autres, de promouvoir la protection et la réalisation des droits de l’homme et des libertés fondamentales aux niveaux national et international.

Article 2

1. Chaque État a, au premier chef, la responsabilité et le devoir de protéger, promouvoir et rendre effectifs tous les droits de l’homme et toutes les libertés fondamentales, notamment en adoptant les mesures nécessaires pour instaurer les conditions sociales, économiques, politique et autres ainsi que les garanties juridiques voulues pour que toutes les personnes relevant de sa juridiction puissent, individuellement ou en association avec d’autres, jouir en pratique de tous ces droits et de toutes ces libertés.

2. Chaque État adopte les mesures législatives, administratives et autres nécessaires pour assurer la garantie effective des droits et libertés visés par la présente Déclaration».

Sous la houlette d’Eleanor Roosevelt et René Cassin, la DUDH proclamait que l’ordre international d’après la Seconde Guerre Mondiale aurait au cœur de ses principes les Droits Humains. Cinquante ans plus tard, la DDDH venait proclamer à son tour que l’ordre international de l’après-Guerre Froide serait celui de la défense des droits des individus par les individus, non pas en dehors ou au mépris de l’État, mais en ayant droit à son soutien.

Si, un quart de siècle plus tard, le constat en la matière ne peut certes être que triste en ce qui concerne les résultats, pour ce qui est de l’urgence de la cause, il ne peut être qu’alarmant.

La WENA, une lumière qui s’éteint ?

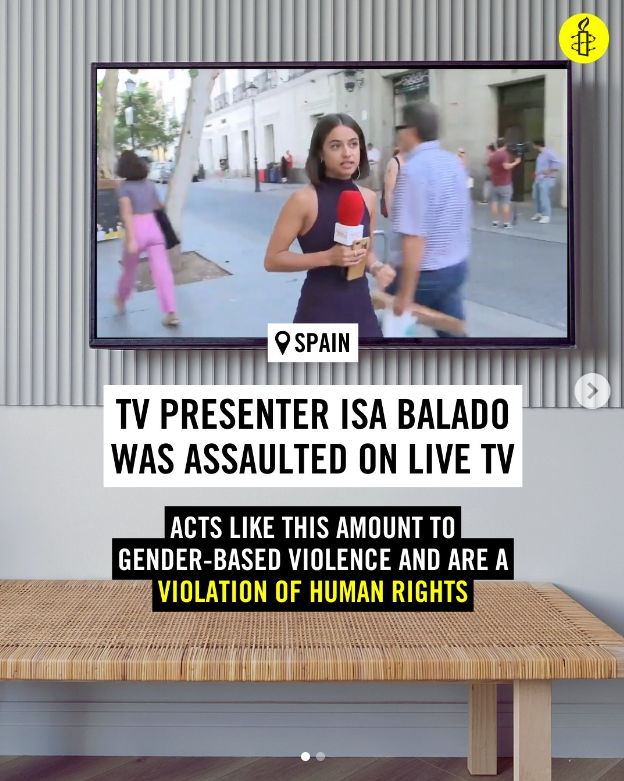

En un quart de siècle, à travers le monde, les DDH se sont élevés et imposés comme une force politique internationale incontournable. Plusieurs Organisations Non-Gouvernementales (ONG) comme FrontLine Defenders et l’International Service for Human Rights (ISHR) consacrent toute leur action à les défendre. Qu’il s’agisse des droits civils et politiques mais aussi des droits sociaux, économiques, culturels, des droits des peuples autochtones et minorités ethniques, des droits liés à l’orientation sexuelle et l’identité de genre, des droits liés à la migration, à l’environnement, au développement, mais aussi des droits des femmes qui se trouvent systématiquement violés dès que tous ces types de violations apparaissent, les DDH sont actifs partout, sur tous les continents, que ce soit à un niveau local, au niveau national voire sur le plan international. Seulement, si la DDDH s’adressait au départ aux pays extérieurs à la WENA (Western Europe and North America, Europe occidentale et Amérique du Nord), une génération plus tard, la région considérée historiquement comme le berceau des Droits Humains peut se voir opposer à son tour la Déclaration tant il n’y est plus acquis d’être un DDH sans devoir en payer le prix.

C’est vrai ne serait-ce que pour un type précis de droits, ceux liés à la migration. Que ce soit aux Etats-Unis, tant sous Donald Trump qu’avec l’administration actuelle de Joe Biden, au Royaume-Uni sous les gouvernements conservateurs et l’impulsion notamment de la ministre Suella Braverman, ou encore en France avec l’adoption récente d’une «loi immigration» fortement empreinte des thèses de l’extrême droite pourtant vaincue à l’élection présidentielle de 2022 et dans l’opposition au Parlement, mais aussi de par les récents succès électoraux de l’extrême droite aux Pays-Bas ou en Suisse, le rejet des migrants et la xénophobie sous toutes ses formes n’ont cessé de progresser dans la WENA. Le rejet des migrants, et avec lui, celui de quiconque les aide à titre humanitaire ou les soutient face à la justice et aux pouvoirs publics. Ces DDH n’échappent plus à la pénalisation, comme ce fut le cas en France pour Martine Landry d’Amnesty International, Loan Torondel, Cédric Herrou et ceux que l’on a surnommés «les 7 de Briançon».

Aux droits des migrants s’ajouteront peut-être bientôt, dans cette WENA oublieuse de ses principes historiques, les droits des femmes. C’est ce que semble démontrer le cas de Vanessa Mendoza Cortés, psychologue et présidente d’une association féministe en Andorre, que le gouvernement de la petite principauté blottie entre France et Espagne a traînée en justice pour être allée s’exprimer sur les droits des femmes devant les Nations Unies – la nouvelle «mode» en matière de représailles contre les DDH étant en effet de pénaliser celles et ceux qui coopèrent avec les agences de l’ONU sur des thématiques locales ou nationales dans leur pays. L’intervention de l’AWC en sa faveur fut la première qui nous vit utiliser, dans l’une de nos interpellations écrites aux gouvernements nationaux en matière de Droits Humains, la langue catalane qui est officielle en Andorre !

Pour Paulo Coelho, «Le monde change par votre exemple et non par votre opinion». Dans une WENA dont les gouvernements sont souvent prompts à donner des leçons en matière de Droits Humains au reste du monde, non dans une moindre mesure aux BRICS dont les membres, issus du Global South ou «Sud Mondial», s’en veulent les porte-parole dans une alternative économique – et politique – à l’hégémonie de la même WENA, un exemple aussi diamétralement opposé à l’opinion professée sera difficilement de nature à impressionner les gouvernements mis en cause, ou a fortiori à rassurer des DDH locaux regardant vers la WENA pour trouver encore inspiration et courage face aux coups portés par leurs gouvernants.

Dans leur essai de 2020 intitulé en anglais The Light that Failed, d’après un ouvrage de Rudyard Kipling intitulé en français La lumière qui s’éteint, Ivan Krastev et Stephen Holmes analysent l’échec de la WENA comme modèle pour les démocraties nouvelles issues de la fin de l’URSS et, a contrario, l’inspiration que d’aucuns dans les pays concernés, à commencer par Viktor Orban en Hongrie, ont fournie aux tenants du populisme en WENA comme Donald Trump. N’en déplaise à ces derniers, si l’on peut tenter de forcer le présent à singer le passé, aucun dictateur, aussi implacable soit-il, ne pourra jamais retourner la flèche du temps vers l’arrière, pas plus que ne le pourra jamais le vote le plus démocratique qui soit. L’an zéro de l’après-Guerre Froide, l’année 1992, est loin derrière nous, comme le sont 1993 et la Conférence de Vienne. Impossible de repartir à zéro sur la base d’un espoir failli. Mais rien n’empêche d’en créer un nouveau, qui soit cette fois pour le monde entier, WENA comprise. Et depuis vingt-cinq ans, un instrument du droit international des Droits Humains existe pour nous y aider. Il serait temps que l’on s’en rende compte et que l’on en fasse bon usage.

L’incarnation en droit international de la Citoyenneté Mondiale

Lorsque la DDDH a été adoptée par l’Assemblée générale de l’ONU, dans ce qui est depuis 1952 sa résidence permanente sur l’East River à New York, l’histoire du mouvement Citoyen du Monde n’a pas retenu la présence de quiconque ayant tenté de camper devant les Nations Unies, ni d’une quelconque tentative d’interruption des débats pour lire une déclaration rédigée par un écrivain célèbre du moment. Tout s’est déroulé dans le calme le plus parfait, la procédure du consensus ayant même permis aux États les moins décidés, voire les plus réticents, de sauver tant soit peu la face. A vrai dire, la DDDH est même une œuvre anonyme, le temps des Roosevelt et des Cassin appartenant à l’histoire et les projets de résolutions étant désormais l’œuvre de professionnels spécialisés, qui sont et resteront donc, à la différence des légendaires promoteurs de la DUDH, des Inconnus dans la maison, pour reprendre le titre d’un ouvrage de Georges Simenon porté à l’écran en 1992 par Georges Lautner – dont ce fut la dernière réalisation – et où Jean-Paul Belmondo, jusqu’alors habitué aux films d’action et aux cascades, interprétait un rôle autrement moins exigeant sur le plan physique puisqu’il y incarnait un avocat.

«Inconnue dans la maison», celle des Citoyens du Monde, c’est ce qu’est la DDDH encore aujourd’hui. Elle qui, pourtant, incarne une forme de Citoyenneté Mondiale sans précédent dans l’histoire, celle d’une consécration de l’action civique individuelle en termes mondiaux, même à un pur niveau local, et de l’exigence de coopération signifiée aux autorités étatiques. Elle qui, à sa manière, incarne la Citoyenneté Mondiale telle que la conçoit l’AWC, «entièrement engagée» auprès des Nations Unies, selon les mots de feu notre Président-fondateur Douglas Mattern, et pour laquelle la Citoyenneté Mondiale se conçoit en plus de la citoyenneté nationale, non pas à la place, ce que rien ne prévoit non plus, du reste, au sein du système des Nations Unies. Elle qui, mieux connue et plus souvent revendiquée, ne pourrait que changer la vie publique pour le meilleur.

La DDDH ne crée pas d’immunité judiciaire ou diplomatique, elle n’est pas une charte de privilèges exonérant le citoyen de ses devoirs envers la communauté où il vit. Héritée du temps où le monde sortait d’une prise en otage permanente de son présent et de son avenir par deux pays le menaçant chacun d’un holocauste nucléaire, elle représente aujourd’hui la traduction en droit international public d’un droit devenu plus fondamental que jamais – celui de ne pas laisser aux seules autorités nationales la protection des droits de chaque personne et de prendre entre ses mains, pour elle-même et pour les autres, la défense de ces droits.

Invoquant lui aussi la Guerre Froide, alors qu’elle se profilait à l’horizon de l’automne 1948, ainsi que ce même droit de prendre sa vie et ses droits entre ses mains, Garry Davis était allé à l’ambassade américaine à Paris rendre sa nationalité et son passeport pour se déclarer Citoyen du Monde. Il s’attendait à être suivi de manière massive, mais si ses idées avaient en effet porté, les ambassades des divers États indépendants de la planète, autrement moins nombreux qu’aujourd’hui en ce temps-là, n’ont en revanche pas vu d’afflux de leurs citoyens venus leur rendre leurs passeports. Depuis un quart de siècle, la DDDH affirme que le civisme mondial n’implique aucune rupture avec l’État-nation et ne se définit pas par la seule possession d’une carte d’identité «mondiale» avec photo, mais par une prise de responsabilité altruiste et universaliste à la portée de toutes et tous.

En un mot, la Citoyenneté Mondiale existe déjà, non pas à titre symbolique mais en pur et vrai droit international. Et parce qu’elle la rend possible, la DDDH, l’inconnue dans la maison des Citoyens du Monde, mérite qu’on la connaisse plus. Et surtout mieux.

Bernard J. Henry est Officier des Relations Extérieures de l’Association of World Citizens.