By Vladimir Ionesov

Anatoly I. Ionesov & Vladimir I. Ionesov,

The Culture of Peace and the Future of Humankind:

Conversations with Outstanding Contemporary Intellectuals

on How to Understand Culture, and What the World Should Be Like in the 21st Century

Vol. I-IV. [Volume I. Nobel Laureates]

Samara-Samarkand: Samara Scientific Center, 2025. 500 p.

The real essence of life is not in what it has,

But in what one believes there should be.

Iosif A. Brodsky (1940-1996)

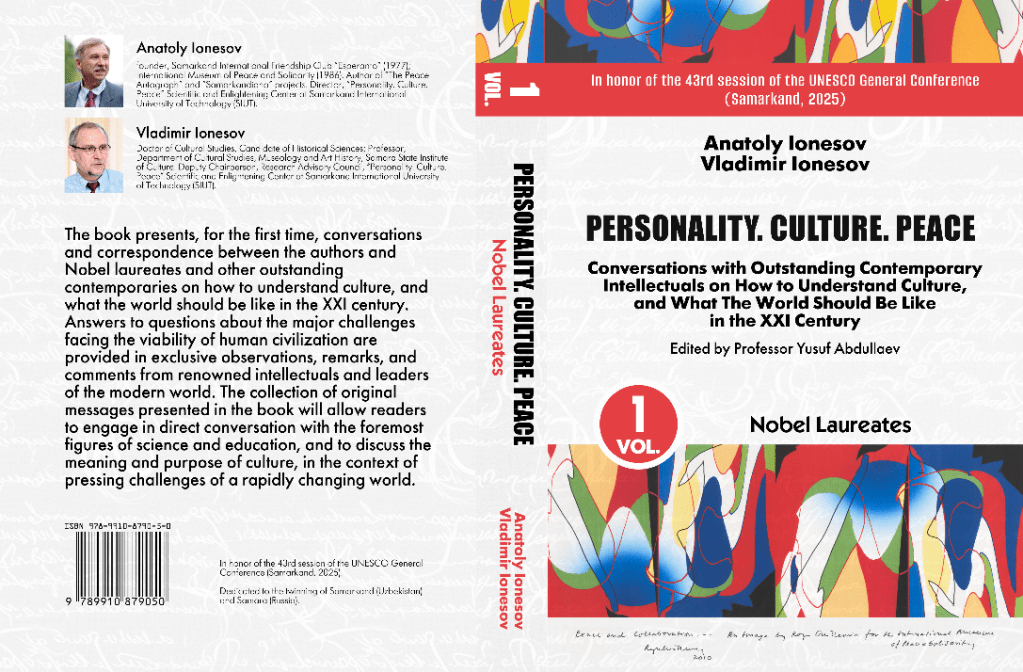

This new book by Anatoly and Vladimir Ionesov contains and presents in four volumes the authors’ extensive materials on the culture of peace and citizen diplomacy, formed on the basis of direct conversation, correspondence, meetings and idea exchanges with outstanding intellectuals of our time. For 40 years, the authors have developed and maintained a dialogue with recognized global leaders in science, education, art, business, politics and sports. This has resulted in a diverse collection of unique written messages and tangible artifacts that have been designed as an International Archives of the Culture of Peace.

The Samarkand International Friendship Club “Esperanto” (Uzbekistan) and the Samara Society for Cultural Studies “Artefact – Cultural Diversity” (Russia), both led by the authors of this publication, created this archive through the organizations’ long-term activities. On the Samarkand site, the International Museum of Peace and Solidarity (1986) was established, and the Peace Autograph Project was initiated; while on the second – Samara city site, the project “Culture of Peace Personalities: People Who Changed the World” (1994) was conceived, launched and implemented. The latter was in direct dialogue on pressing issues of the philosophy of peacemaking and the viability of modern civilization with recognized experts in the field.

Thanks to these joint projects and other types of partnership activities, it was possible to include the two sister cities – Samarkand, the ancient pearl of the East, and Samara, the ‘Space Capital’ of Russia, in the dialogue with the wider world. Through correspondence, interviews, meetings, conversations, creative projects, scientific connections, educational exchange, and other cultural practices of citizen diplomacy, communication was established with contemporaries who, through their ideas, visions, achievements, and professional experience, showed how life can be changed for the better. The authors, using the example of these personalities, their spoken or written word, proposed thoughts, insightful intuition and skillfully embodied deeds, sought to testify to unique examples of personal selfless devotion in culture. And, thereby, convey their main message: any individual may cope with the challenges of the changing world if he or she relies on knowledge, creativity, morality, humanism and free thinking.

At different stages of the project, participants in dialogue with the authors included thousands of individuals. Their visions for solving the most pressing challenges help to better understand how to build and promote a culture of peace, a philosophy of nonviolence and tolerance in the multicultural diversity of humankind. This way we discussed multiple problems the world is facing today with the people who have probably managed to implement those principles into life most fully.

The participants in the direct conversation were a variety of personalities from a Nobel Prize laureate to a simple teacher of a provincial school, from an outstanding politician to an ordinary citizen, from a famous preacher to an inconspicuous volunteer, from a professional traveler and explorer to an ordinary wanderer and creator. Each of them has their own view of the world, their own visions, interests, values, preferences. Their answers to questions, remarks and comments are unequal, as are their biographies and professional activities. In short, they are as varied as life itself.

The materials included in each volume of this publication are divided into two main sections 1. Answers to Questions, Letters and Reflections and 2. Remarks, Comments, Greetings, and two Appendices. The personal messages are placed in alphabetical order without chronological sequence. Each separate block consists of three parts: information about the person, a photo with an autograph or gift inscription, and the text of the reply. All correspondence is represented by original texts – personal messages addressed to the authors in Samarkand or Samara. The Appendix provides a consolidated list of Nobel Prize laureates who have sent their feedback (messages, etc.) to the authors and a small photo chronicle.

The first volume consists of replies, letters, remarks and comments of 72 Nobel Prize laureates representing 20 countries of the world (Argentina, Belgium, Great Britain, East Timor (Timor Leste), China (territory of Tibet), Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, India, Ireland, Japan, Mexico, Nigeria, Netherlands, Russia, former USSR, South Africa, Switzerland, USA). All the authors of the messages placed in the book are arranged in alphabetical order.

Our interlocutors are distinguished intellectuals in the field of scientific research whose works have changed the world for the better through revolutionary inventions and major contributions to the culture and development of society. Among the intellectual leaders of our time included in this volume who have shared with the authors their visions on how to understand culture and what the world should be like in the twenty-first century are Nobel Prize laureates in Chemistry (19), Physics (15), Physiology or Medicine (11), Economics (7), Literature (4), and for promoting world Peace (16).

The authors of the book are grateful to their distinguished interlocutors, who, in addition to answering questions, have also kindly provided the texts of their articles and other materials as expanded commentary on a given topic for translation and inclusion in this edition.

The book concludes with a list of all Nobel laureates who responded to the dialogue with the authors, including the names of those whose comments and greetings, although not included in this edition, have become an important and inspiring part of the project.

In total, responses were received from 253 Nobelists in six fields (including three scientists who were awarded this prize twice): 49 laureates in chemistry, 68 – in physics, 63 – in physiology or medicine, 30 – in economics, 13 – in literature and 30 participants of the project were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

It should be noted that the “Culture of Peace Personalities” project, launched and implemented by the authors, inspired the creation and suggested the name of the newly established “Personality. Culture. Peace” Scientific and Enlightening Center at Samarkand International University of Technology (SIUT). It is gratifying that it was the Center that became the main venue for the completion of such a significant book project.

The authors consider this publication as another step in strengthening partnership and twinning between Samarkand and Samara. They hope that their work will contribute to the development of not only the two sister cities, but also of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). In this regard, it is noteworthy that by the decision of the CIS Council of Heads of State, Samarkand has acquired another landmark status for itself – becoming the cultural capital of the Commonwealth in 2024.

When the first volume was ready to go to press, the authors of the book received a message from a Canadian scientist, Nobel Laureate in Physics (2015) Arthur B. McDonald (b. 1943). It contained remarkable words that insightfully reflect the main idea behind this publication: “The openness and international cooperation between basic scientists seeking and understanding of the world we live in can be a model for everyone and a direction for world peace”. – Arthur B. McDonald, March 23, 2023, Canada.

It remains to be hoped that an interested reader, within the dialogue space with the authors and participants of this edition, will find useful answers to pressing questions and gain clarity on complex issues in the current agenda of our turbulent times.

Anatoly Ionesov, founder, Samarkand International Friendship Club “Esperanto” (1977); International Museum of Peace and Solidarity (1986). Author of “The Peace Autograph” and “Samarkandiana” projects. Director, “Personality. Culture. Peace” Scientific and Enlightening Center of Samarkand International University of Technology (SIUT).

Vladimir Ionesov, Doctor of Cultural Studies, Candidate of Historical Sciences; Professor, Department of Cultural Studies, Museology and Art History, Samara State Institute of Culture. Developer of the concept of cultural transformation and models of civilization viability in transition. Full member of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts. Deputy Chairperson, Research Advisory Council, “Personality. Culture. Peace” Scientific and Enlightening Center of Samarkand International University of Technology (SIUT).