By René Wadlow

(An earlier version of this piece was published on Transcend Media Service.)

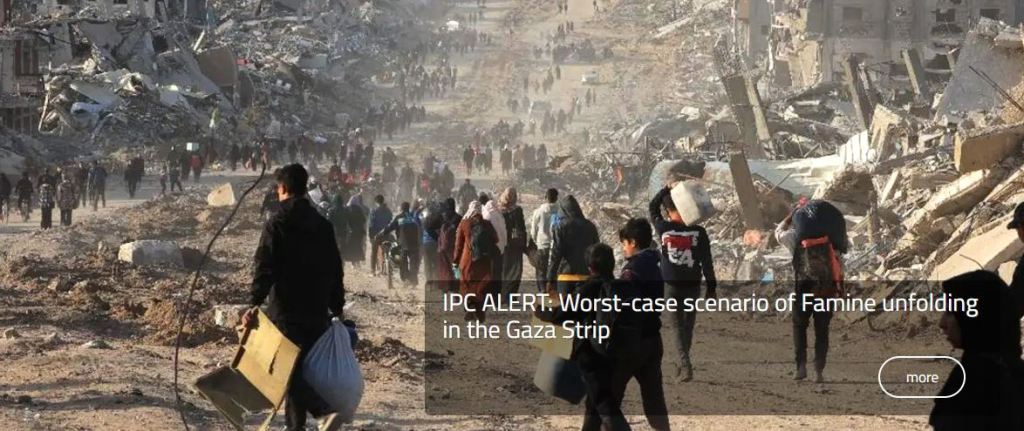

On September 29, 2025, United States (U.S.) President Donald Trump presented his 20-point Peace Plan for the Gaza Strip which sets out a ceasefire, a release of hostages held by the Palestinian Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas) and its armed allies, a dismantling of Hamas’ military structures, the withdrawal of Israeli troops, and the creation of an international “Board of Peace” to supervise the administration of the Gaza Strip with President Trump as chair and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair as the chief administrator. Relief supplies to meet human needs would be facilitated. The plan concerns only the Gaza Strip and does not deal directly with the West Bank where tensions are strong.

The plan has been presented to the Israeli Prime Minister, Benyamin Netanyahu who was in Washington, D.C. and to Arab leaders who were at the United Nations in New York. The plan has been given to Hamas’ leaders through intermediaries, but Hamas’ leadership has been severely weakened by deaths. Thus, it is not clear how decision-making will be done by Hamas. The plan has also been presented to the Palestinian Authority (PA) in Ramallah, led by Mahmoud Abbas, but the PA would play no part in the Gaza Strip’s future. The plan is being widely discussed, but no official decisions have been announced.

The Gaza Peace Plan has some of the approach of the Transcend proposals (1) with, in addition, the possibility of violence if the Gaza Peace Plan is not carried out. Threats of violence are not among Transcend’s tools. One of the distinctive aspects of Transcend and the broader peace research movement is to present specific proposals for transcending current conflicts through an analysis of the roots of the conflict, the dangers if the conflict continues as it is going, and then the measures to take. (2) The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is one which presents dangers to the whole region if creative actions are not taken very soon. We must act now. We cannot wait for President Trump to do it for us.

Notes:

(1) Transcend Media Service, “The Time Has Arrived for a Comprehensive Middle East Peace”, Jeffrey D. Sachs and Sybil Fares, July 7, 2025.

(2) See:

Johan Galtung, The True Worlds (New York/The Free Press/1980/469pp)

John Paul Lederach, Preparing for Peace (Syracuse, NY/Syracuse University Press/1995/133pp)

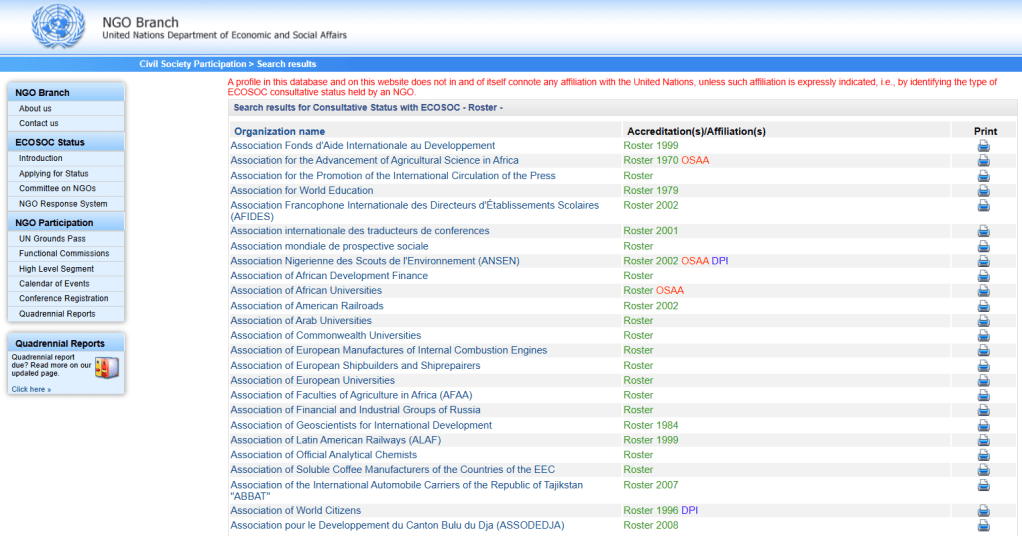

Prof. René Wadlow is President of the Association of World Citizens.