OSCE: STRAINS AND RENEWAL IN THE SECURITY COMMUNITY

By René Wadlow

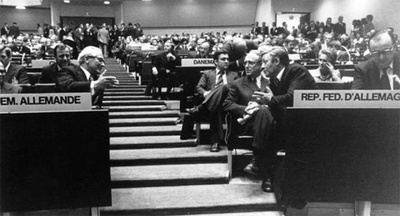

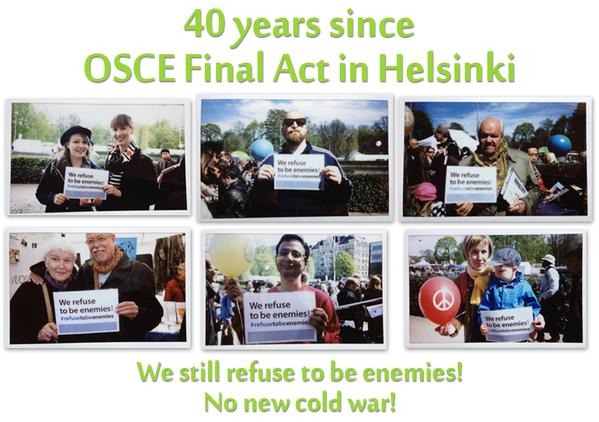

On August 1, 2015, the Helsinki Final Act, the birth certificate of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) turned 40. The Final Act signed in Helsinki’s Finlandia Hall was the result of three years of nearly continuous negotiations among government representatives meeting for the most part in Geneva, Switzerland as well as years of promotion of better East-West relations by non-governmental peace builders.

Basically, one can date the planting of the seeds that grew into the OSCE as 1968 in two cities: Paris and Prague. The student-led demonstrations in Paris which sent shock waves to other university centers from California to Berlin showed that under a cover of calm, there was a river of demands and desires for a new life, a more cooperative and creative way of life.

In Prague, the Prague Spring of internal reforms and demands for a freer European society was met by the tanks of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact in August. Yet some far-sighted individuals saw that 1968 was a turning point in European history and that there could be no return to the 1945 divisions of two Europes with the Berlin Wall as the symbol of that division. Thus, in small circles, there were those who started asking “Where do we go from here?”

A Security Community: A Halfway House

In 1957, Karl W. Deutsch (1912-1992) published an important study, Political Community and the North Atlantic Area (Princeton University Press). Karl Deutsch was born to a German-speaking family in Prague in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His family was active in socialist party politics and became strongly anti-Nazi. Seeing what might happen, Deutsch and his wife left Prague in 1939 for the USA where he became a leading political science-international relations professor. I knew Karl Deutsch in the mid-1950s when I was a university student at Princeton, and he was associated with a Center on International Organization at Princeton. It was there that he was developing his ideas on types of integration among peoples and States and that he coined the term “security community” to mean a group of people “believing that they had come to agreement on at least one point that common social problems must and can be resolved by processes of peaceful change.” For Deutsch, the concept of a security community could be applied to people coming together to form a State: His approach was much used in the 1960s in the study of “nation building” especially of post-colonial African States. A “security community” could also be a stage in relations among States as the term has become common in OSCE thinking. For Deutsch, a security community was a necessary halfway house before the creation of a State or a multi-State federation. Deutsch stressed the need for certain core values which created a sense of mutual identity and loyalty leading to self-restraint and good-faith negotiations to settle disputes.

Core values established and quickly disappeared

During the negotiations leading to the Helsinki Final Act, a set of 10 core values or commitments were set out, sometimes called the OSCE Decalogue after the “Ten Commandments”. “Sovereign equality, respect for the rights inherent in sovereignty and non-intervention in internal affairs” set the framework as well as the limitations of any efforts toward a supranational institution. The two other related core values were “the territorial integrity of States and the inviolability of frontiers.”

The core values were not so much “values” as a reflection of the status quo of the Cold War years. By the time that the Charter of Paris for a New Europe was signed in November 1990, marking the formal end of the Cold War, “territorial integrity and the inviolability of frontiers” as values had disappeared.

The 1990s saw the breakup of two major European federations − that of Yugoslavia and the USSR. Most of the work of the OSCE has been devoted to the consequences of these two breakups. Yugoslavia broke into nearly all the pieces that it could with a few exceptions. I had been asked to help support the independence of Sandzak, a largely Muslim area in Serbia and part of Montenegro. I declined, having thought at the time that with a few modifications the Yugoslav federation could be kept together. I was wrong, and the OSCE is still confronted by tensions in Kosovo, renewed tensions in Macedonia, an unlikely form of government in Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as social issues of trafficking in persons, arms, drugs and uncontrolled migration.

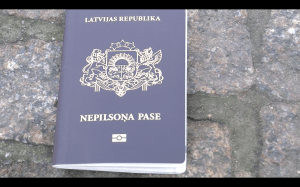

The breakup of the Soviet Union has led to a full agenda of OSCE activities. The republics of the Soviet Union had been designed by Joseph Stalin, then Commissioner for Nationalities so that each republic could not become an independent State but would have to look to the central government for security and socio-economic development. Each Soviet republic had minority populations though each was given the name of the majority or dominant ethnic group called a “nationality”.

With the breakup of the Soviet Union, there have been recurrent issues involving the degree of autonomy of geographic space and the role of minorities. The conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh had already started before the breakup, but continues to this day with its load of refugees, displaced persons and the calmer but unlikely twin, the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic. Moldova and Transdniestria remain a “frozen conflict” with a 1992 ceasefire agreement. The armed conflicts in Chechnya and violence in Dagestan highlighted conflicts within the Russian Federation. The 2008 “Guns of August” conflict over South Ossetia between Russia and Georgia showed that autonomy issues could slip out of control and have Europe-wide consequences.

A Cloudy Cristal Ball

Predictions, especially about the future, are always difficult. In 2013, the OSCE Chairperson-in-Office, the then Minister for Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, Leonid Kazhara, said “We wish to contribute to the establishment of the Euro-Atlantic and Eurasian security community free of dividing lines, conflicts, spheres of influence and zones with different levels of security … There is a pressing need to, first of all, change our mindsets from confrontational thinking to a cooperative approach. I am confident that Ukraine, with its rich history, huge cultural heritage and clear European aspirations is well placed for carrying out this mission.”

Today, Ukraine’s rich history has a new chapter, recreating old dividing lines and spheres of influence. The shift in “ownership” of Crimea indicates that “territorial integrity of States” is a relative commitment. The large number of persons going to Russia as refugees and to west Ukraine as internally-displaced persons recalls the bad days of displacement of the Second World War. NATO has dangerously over-reacted to events in Ukraine.

It is not clear that the current leaders of the 57 governments of the OSCE have the wisdom or skills to lead to a renewal of the Security Community. Yet when one looks at the photos of the government leaders who did sign the Helsinki Final Act 40 years ago, there are few faces indicating wisdom or diplomatic skills so perhaps all is not lost today. Very likely, as in the period between the events of 1968 and the start of government negotiations in 1972, there will need to be nongovernmental voices setting out new ideas and creating bridges between people.

Prof. René Wadlow is President and Chief Representative to the United Nations Office at Geneva of the Association of World Citizens.