RATKO MLADIĆ: ARREST AND COMING TRIAL – A STEP FORWARD FOR WORLD LAW

By René Wadlow

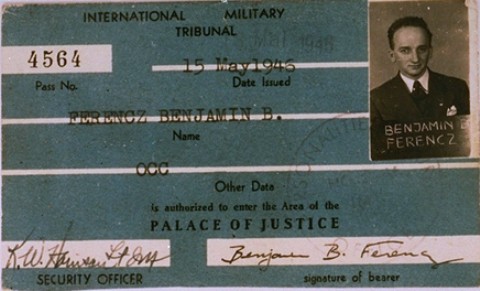

On May 26, 2011, President Boris Tadić of Serbia announced the arrest of General Ratko Mladić, the Yugoslav general become head of the Bosnian Serb forces of Republika Srpska. General Mladić had been charged by the War Crimes Tribunal for ex-Yugoslavia in the Hague for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes and thus should be sent from Belgrade to the Hague to stand trial shortly. General Mladić is particularly charged with commending the 1992-1995 siege of Sarajevo during which much of the city was destroyed and some 10,000 persons killed, often shot by snipers. The genocide charge arises mainly from the killing in July 1995 of some 8,000 Muslim men at Srebrenica which had been declared a neutral safe haven guarded by UN troops.

Mladić had been forced from his position in Republika Srpska after the 1995 Dayton Agreement, largely facilitated by the US envoy Richard Holbrooke. Mladić moved to Serbia and lived mostly in Belgrade, having changed his name. He was arrested at the farm of a cousin some 50 miles north of Belgrade in the Vojvodina area. His arrest and trial was one of the conditions set by the European Union for advancing with negotiations on Serbia joining the EU. Negotiations are now at a serious stage, and the arrest of Mladić was necessary to open the door further. Mladić kept out of sight, but he was not hiding. He had supporters in the Serbian army, police and in certain nationalist political circles. Thus an arrest earlier would not have been worth the political outcries and tensions an arrest might have provoked. Now, when EU membership and the economic future of the country are at stake, his arrest is not a very high price to pay.

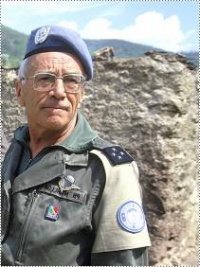

Ratko Mladić, here as the Bosnian Serb forces' top general during the civil war in Bosnia-Herzegovina (1922-1995).

It is not really satisfaction when one sees those who have betrayed one’s proposals are finally taken down. However, there is a sense of “closure” – a recognition that karma is finally at work. I did not know Ratko Mladić but saw him a number of times in the halls of the Palais des Nations — the European Headquarters of the United Nations (UN). I was in contact with Radovan Karadžić, the political head of the Bosnian Serbs — officially Prime Minister of Republika Srpska. I had been asked to be an advisor to Karadžić on UN procedures when negotiations began in Geneva in 1992. After discussions, I turned down the offer although it would have been a possibility to be a direct participant in the negotiations.

Whatever credibility I had in the Yugoslav conflict came from being a neutral and not linked to one side, although I was generally seen as pro-Serb. My first efforts had been to help Milan Babić, the leader of the Serb enclave in Croatia called Krajina. I had Babić address the UN Commission on Human Rights in February 1991 to warn of the consequences if Yugoslavia broke up. His presentation was filmed and widely shown on Yugoslav TV. I am still convinced that had his warning been taken seriously, things might have been different. However, the Commission on Human Rights was not really equipped to deal with “early warning”, and nothing was done until fighting broke out in June 1991.

Here with then General Ratko Mladić, former Bosnian Serb political leader Radovan Karadžić.

In June, Krajina declared its independence from Croatia, calling itself the Republic of Serbian Krajina. Babić was named Prime Minister. From August to December 1991, Serbs from Krajina killed hundreds of Croats and drove some 80,000 from their homes. Ratko Mladić was the head of the Krajina forces at the time and a close co-worker with Babić.

In 1992, Babić was eased out of power by behind-the-scenes pressures by Prime Minister of Serbia, Slobodan Milosevic, who wanted someone with a less independent character, at which time Mladić left Krajina and went to Bosnia where he had been born.

In 2004 Babić was sentenced to 13 years in prison for war crimes by the Yugoslav War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague and shortly afterwards committed suicide.

On July 11, 1995, General Ratko Mladić and his troops stormed the Bosnian Safe Haven of Srebrenica. With the most unwelcome participation of UN peacekeepers there, they secured the place for the Bosnian Serb army and took some 7,000 unarmed Bosnian civilians to their death.

In March 1992, Bosnia-Herzegovina declared its independence from Yugoslavia, and at the same time, Republika Srpska declared itself independent under the leadership of Radovan Karadžić. Many at the time questioned the wisdom of a unilateral splitting of Bosnia, but Mladić said “The existence of the Republika Srpska may be contested internationally, but the existence of its army cannot be contested. The Republika Srpska exists because we have our territory, our nation, our government and all the attributes of a state. Whether they acknowledge it or not — that’s their problem. The army is the fact.”

A month later, in April 1992, the siege of Sarajevo began with Ratko Mladić in charge of the Serb forces. The siege was to illustrate that a multi-ethnic society could not exist, Sarajevo being the Yugoslav city with the most ethnically-mixed population.

I had been in Belgrade in 1991 at the start of the Yugoslav fighting, just at the time of the fall of Vukovar, the first major battle, to see if NGOs could play any role in conflict reduction. But once the fighting had broken out there was really nothing that NGOs could do to prevent the spread of the conflict. The International Committee of the Red Cross tried, with great difficulty, to maintain some humanitarian efforts, but NGO conflict mediation was not really possible.

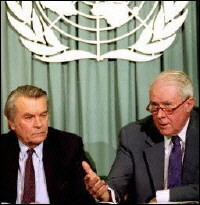

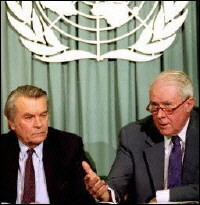

In September 1992, with fighting still going on, the Geneva Peace Conference on Bosnia began at the UN headquarters under the co-leadership of Lord David Owen on behalf of the EC and Mr. Cyrus Vance, former U. S. Secretary of State for the UN. Vance later withdrew, discouraged by the lack of progress and was replaced by Thorvald Stoltenberg, a former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Norway.

Lord David Owen, Special Representative of the European Community for Bosnia-Herzegovina, and the UN Special Envoy, former U. S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance.

Late in 1992, as fighting was increasing and political proposals for the future of Bosnia were bogged down, David Arnott, an English Buddhist who had been working with me on Burma issues and I were the first to propose in the UN Commission on Human Rights and in a text sent to the members of the UN Security Council the creation of a number of security zones or “safe areas” within Bosnia-Herzegovina. I had been working closely with Tadeusz Mazowiecki, a former Prime Minister of Poland, who was the Special Rapporteur of the Commission on Human Rights on ex-Yugoslavia. In his November 1992 Report to the Commission, he had proposed the establishment of a security zone encompassing Sarajevo and its airport in order to facilitate the delivery of humanitarian supplies.

Building on this proposal, in an oral statement of December 1, 1992 to the “Special Session of the Commission on Human Rights devoted to Human Rights in Former Yugoslavia”, I stressed the need to create a larger number of safe havens and emphasized “that the declaration of protected Safe Haven Zones is an interim arrangement with a humanitarian purpose and in no way reduces the urgent and imperative need to find negotiated political solutions.”

Safe havens, called neutralized zones, are provided for in article 15 of the 4th Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949. On October 30, 1992, the International Committee of the Red Cross had proposed that “protected zones be set up for the civilian population at risk, away from combat areas. They would not be intended for the inhabitants of besieged towns for whose protection other solutions should be found, such as a cessation of hostilities.” This was basically a call for protected refugee camps while ours was for “protected cities” since ‘cessation of hostilities’ were not in the cards.

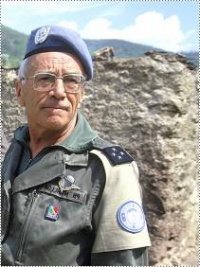

General Sir Michael Rose, the British senior military man who in 1994 served as Commander of the Bosnian segment of the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR Bosnia). When the Bosnian Serb army attacked a UN-declared Safe Haven for the first time (that was Goražde in April 1994), General Rose and his UNPROFOR troops stood idle and let the Bosnian Serbs invade the city.

Thus our proposal was not original but rather what was needed for the hour. On April 16, 1993, the UN Security Council proclaimed Srebrenica a safety zone and on May 6 added Sarajevo, Žepa, Goražde, Bihać and Tuzla to the list. Our proposal was quoted by the then Ambassador of Afghanistan, Mr. Farhadi, during the debate on safe havens.

Thus I followed with interest how the safe havens were put into place. Srebrenica had been a middle-sized town of 6,000 prior to the fighting. It had grown to over 70,000 as families left the countryside for the relative safety of the town; infrastructure, however, could not keep up.

In July 1995, the “safe havens” of Žepa and Srebrenica were taken over by the forces led by Ratko Mladić. The UN forces led by soldiers from the Netherlands did not try to resist. A month earlier in June, UN forces had been taken hostage for two weeks but finally were released. Although NATO planes were dropping bombs on Serb positions at the time, it is not clear that any NATO forces would have come to the defense of the Dutch. The UN troops stood by as Mladić separated the women and children from the men. He had his soldiers kill some 8,000 male prisoners and had their bodies put into mass graves.

General Philippe Morillon, the French peacekeeper whose efforts to protect the UN-designated Safe Havens quickly made him a living legend in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

There had been so many violations of the laws of war and human rights in the Yugoslav conflicts, that there was not much public outcry at the time, although Tadeusz Mazowiecki resigned his UN position as Special Rapporteur writing to the UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali and making his letter public that his resignation was forced by the “horrendous tragedy which has beset the population of those ‘safe havens’ guaranteed by international agreement…I believe we have a certain hypocrisy as far as Bosnia is concerned when we are claiming to defend it but in fact we are abandoning it. The same goes for hypocrisy about the protection of human rights. I hope that my decision will also be understood as a protest against this hypocrisy.”

The wheels of karma turn slowly. As there is no longer anything at stake, more people today will agree that killing people who thought that they were protected in UN-proclaimed safe havens is not a good thing. There have been no new proposals for safe havens since and thus none has been created. I still think that it was a good idea at the time. Yet I share the observation of Michèle Mercier who had been for a long time part of the International Committee of the Red Cross team in former Yugoslavia “The word most frequently heard in the ranks of humanitarian workers is frustration. Their leaders are powerless to settle by themselves the problems involved with security and they have worn themselves out negotiating and renegotiating with opposite numbers of the most unlikely kind agreements that lose all their meaning before they are reached.” (1)

René Wadlow is Senior Vice-President and Chief Representative to the United Nations Office at Geneva of the Association of World Citizens.

(1) Michèle Mercier Crimes Without Punishment: Humanitarian Action in Former Yugoslavia (London: Pluto Press, 1995, p. 165)