By Lawrence Wittner

Lesley M. M. Blume, Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World.

New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020

In this crisply-written, well-researched book, Lesley Blume, a journalist and biographer, tells the fascinating story of the background to John Hersey’s pathbreaking article, “Hiroshima,” and of its extraordinary impact upon the world.

In 1945, although only 30 years of age, Hersey was a very prominent war correspondent for Time magazine—a key part of publisher Henry Luce’s magazine empire—and living in the fast lane. That year, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his novel, A Bell for Adano, which had already been adapted into a movie and a Broadway play. Born the son of missionaries in China, Hersey had been educated at upper class, elite institutions, including the Hotchkiss School, Yale, and Cambridge. During the war, Hersey’s wife, Frances Ann, a former lover of young Lieutenant John F. Kennedy, arranged for the three of them to get together over dinner. Kennedy impressed Hersey with the story of how he saved his surviving crew members after a Japanese destroyer rammed his boat, PT-109. This led to a dramatic article by Hersey on the subject—one rejected by the Luce publications but published by the New Yorker. The article launched Kennedy on his political career and, as it turned out, provided Hersey with the bridge to a new employer – the one that sent him on his historic mission to Japan.

Blume reveals that, at the time of the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Hersey felt a sense of despair—not for the bombing’s victims, but for the future of the world. He was even more disturbed by the atomic bombing of Nagasaki only three days later, which he considered a “totally criminal” action that led to tens of thousands of unnecessary deaths.

Most Americans at the time did not share Hersey’s misgivings about the atomic bombings. A Gallup poll taken on August 8, 1945 found that 85 percent of American respondents expressed their support for “using the new atomic bomb on Japanese cities.”

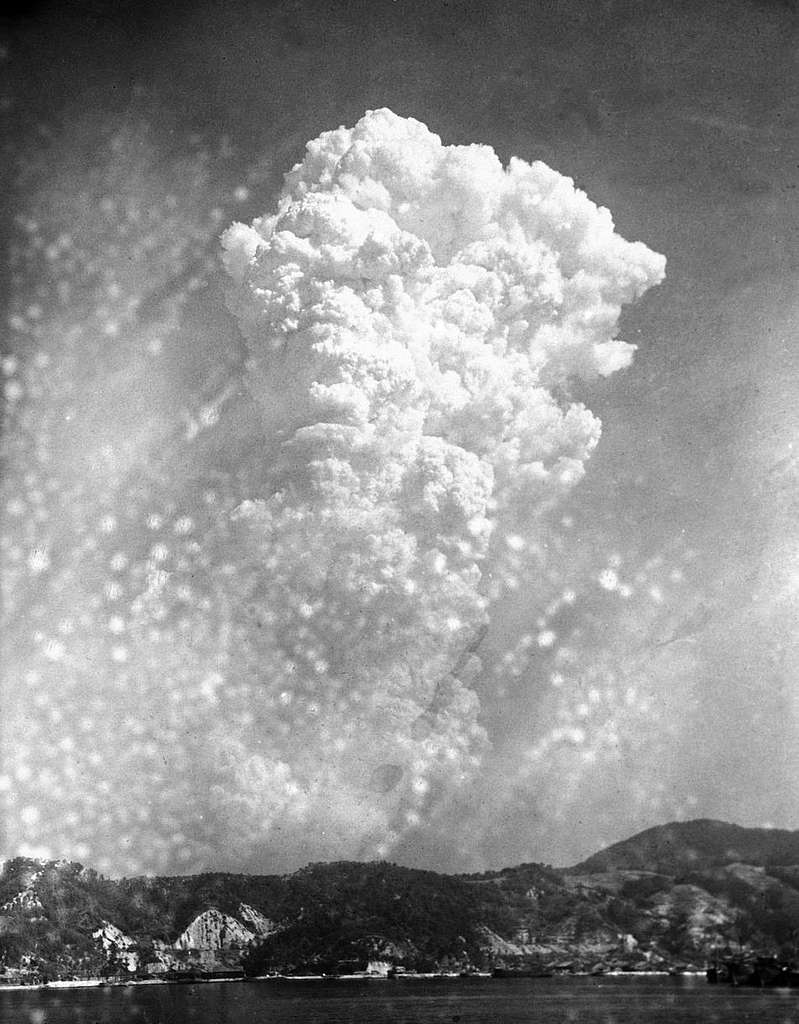

Blume shows very well how this approval of the atomic bombing was enhanced by U.S. government officials and the very compliant mass communications media. Working together, they celebrated the power of the new American weapon that, supposedly, had brought the war to an end, by producing articles lauding the bombing mission and pictures of destroyed buildings. What was omitted was the human devastation, the horror of what the atomic bombing had done physically and psychologically to an almost entirely civilian population—the flesh roasted off bodies, the eyeballs melting, the terrible desperation of mothers digging with their hands through the charred rubble for their dying children.

The strange new radiation sickness produced by the bombing was either denied or explained away as of no consequence. “Japanese reports of death from radioactive effects of atomic bombing are pure propaganda,” General Leslie Groves, the head of the Manhattan Project, told the New York Times. Later, when, it was no longer possible to deny the existence of radiation sickness, Groves told a Congressional committee that it was actually “a very pleasant way to die.”

When it came to handling the communications media, U.S. government officials had some powerful tools at their disposal. In Japan, General Douglas MacArthur, the supreme commander of the U.S. occupation regime, saw to it that strict U.S. military censorship was imposed on the Japanese press and other forms of publication, which were banned from discussing the atomic bombing. As for foreign newspaper correspondents (including Americans), they needed permission from the occupation authorities to enter Japan, to travel within Japan, to remain in Japan, and even to obtain food in Japan. American journalists were taken on carefully controlled junkets to Hiroshima, after which they were told to downplay any unpleasant details of what they had seen there.

In September 1945, U.S. newspaper and magazine editors received a letter from the U.S. War Department, on behalf of President Harry Truman, asking them to restrict information in their publications about the atomic bomb. If they planned to do any publishing in this area of concern, they were to submit the articles to the War Department for review.

Among the recipients of this warning were Harold Ross, the founder and editor of the New Yorker, and William Shawn, the deputy editor of that publication. The New Yorker, originally founded as a humor magazine, was designed by Ross to cater to urban sophisticates and covered the world of nightclubs and chorus girls. But, with the advent of the Second World War, Ross decided to scrap the hijinks flavor of the magazine and begin to publish some serious journalism.

As a result, Hersey began to gravitate into the New Yorker’s orbit. Hersey was frustrated with his job at Time magazine, which either rarely printed his articles or rewrote them atrociously. At one point, he angrily told publisher Henry Luce that there was as much truthful reporting in Time magazine as in Pravda. In July 1945, Hersey finally quit his job with Time. Then, late that fall, he sat down with William Shawn of the New Yorker to discuss some ideas he had for articles, one of them about Hiroshima.

Hersey had concluded that the mass media had missed the real story of the Hiroshima bombing. And the result was that the American people were becoming accustomed to the idea of a nuclear future, with the atomic bomb as an acceptable weapon of war. Appalled by what he had seen in the Second World War—from the firebombing of cities to the Nazi concentration camps—Hersey was horrified by what he called “the depravity of man,” which, he felt, rested upon the dehumanization of others. Against this backdrop, Hersey and Shawn concluded that he should try to enter Japan and report on what had really happened there.

Getting into Japan would not be easy. The U.S. Occupation authorities exercised near-total control over who could enter the stricken nation, keeping close tabs on all journalists who applied to do so, including records on their whereabouts, their political views, and their attitudes toward the occupation. Nearly every day, General MacArthur received briefings about the current press corps, with summaries of their articles. Furthermore, once admitted, journalists needed permission to travel anywhere within the country, and were allotted only limited time for these forays.

Even so, Hersey had a number of things going for him. During the war, he was a very patriotic reporter. He had written glowing profiles about rank-and-file U.S. soldiers, as well as a book (Men on Bataan) that provided a flattering portrait of General MacArthur. This fact certainly served Hersey well, for the general was a consummate egotist. Apparently as a consequence, Hersey received authorization to visit Japan.

En route there in the spring of 1946, Hersey spent some time in China, where, on board a U.S. warship, he came down with the flu. While convalescing, he read Thornton Wilder’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey, which tracked the different lives of five people in Peru who were killed when a bridge upon which they stood collapsed. Hersey and Shawn had already decided that he should tell the story of the Hiroshima bombing from the victims’ point of view. But Hersey now realized that Wilder’s book had given him a particularly poignant, engrossing way of telling a complicated story. Practically everyone could identify with a group of regular people going about their daily routines as catastrophe suddenly struck them.

Hersey arrived in Tokyo on May 24, 1946, and two days later, received permission to travel to Hiroshima, with his time in that city limited to 14 days.

Entering Hiroshima, Hersey was stunned by the damage he saw. In Blume’s words, there were “miles of jagged misery and three-dimensional evidence that humans—after centuries of contriving increasingly efficient ways to exterminate masses of other humans—had finally invented the means with which to decimate their entire civilization.” Now there existed what one reporter called “teeming jungles of dwelling places . . . in a welter of ashes and rubble.” As residents attempted to clear the ground to build new homes, they uncovered masses of bodies and severed limbs. A cleanup campaign in one district of the city alone at about that time unearthed a thousand corpses. Meanwhile, the city’s surviving population was starving, with constant new deaths from burns, other dreadful wounds, and radiation poisoning.

Given the time limitations of his permit, Hersey had to work fast. And he did, interviewing dozens of survivors, although he eventually narrowed down his cast of characters to six of them.

Departing from Hiroshima’s nightmare of destruction, Hersey returned to the United States to prepare the story that was to run in the New Yorker to commemorate the atomic bombing. He decided that the article would have to read like a novel. “Journalism allows its readers to witness history,” he later remarked. “Fiction gives readers the opportunity to live it.” His goal was “to have the reader enter into the characters, become the characters, and suffer with them.”

When Hersey produced a sprawling 30,000 word draft, the New Yorker’s editors at first planned to publish it in serialized form. But Shawn decided that running it this way wouldn’t do, for the story would lose its pace and impact. Rather than have Hersey reduce the article to a short report, Shawn had a daring idea. Why not run the entire article in one issue of the magazine, with everything else—the “Talk of the Town” pieces, the fiction, the other articles and profiles, and the urbane cartoons—banished from the issue?

Ross, Shawn, and Hersey now sequestered themselves in a small room at the New Yorker’s headquarters, furiously editing Hersey’s massive article. Ross and Shawn decided to keep the explosive forthcoming issue a top secret from the magazine’s staff. Indeed, the staff were kept busy working on a “dummy” issue that they thought would be going to press. Contributors to that issue were baffled when they didn’t receive proofs for their articles and accompanying artwork. Nor were the New Yorker’s advertisers told what was about to happen. As Blume remarks: “The makers of Chesterfield cigarettes, Perma-Lift brassieres, Lux toilet soap, and Old Overholt rye whiskey would just have to find out along with everyone else in the world that their ads would be run alongside Hersey’s grisly story of nuclear apocalypse.”

However, things don’t always proceed as smoothly as planned. On August 1, 1946, President Truman signed into law the Atomic Energy Act, which established a “restricted” standard for “all data concerning the manufacture or utilization of atomic weapons.” Anyone who disseminated that data “with any reason to believe that such data” could be used to harm the United States could face substantial fines and imprisonment. Furthermore, if it could be proved that the individual was attempting to “injure the United States,” he or she could “be punished by death or imprisonment for life.”

In these new circumstances, what should Ross, Shawn, and Hersey do? They could kill the story, water it down, or run it and risk severe legal action against them. After agonizing over their options, they decided to submit Hersey’s article to the War Department—and, specifically, to General Groves—for clearance.

Why did they take that approach? Blume speculates that the New Yorker team thought that Groves might insist upon removing any technical information from the article while leaving the account of the sufferings of the Japanese intact. After all, Groves believed that the Japanese deserved what had happened to them, and could not imagine that other Americans might disagree. Furthermore, the article, by underscoring the effectiveness of the atomic bombing of Japan, bolstered his case that the war had come to an end because of his weapon. Finally, Groves was keenly committed to maintaining U.S. nuclear supremacy in the world, and he believed that an article that led Americans to fear nuclear attacks by other nations would foster support for a U.S. nuclear buildup.

The gamble paid off. Although Groves did demand changes, these were minor and did not affect the accounts by the survivors.

On August 29, 1946, copies of the “Hiroshima” edition of the New Yorker arrived on newsstands and in mailboxes across the United States, and it quickly created an enormous sensation, particularly in the mass media. Editors from more than thirty states applied to excerpt portions of the article, and newspapers from across the nation ran front-page banner stories and urgent editorials about its revelations. Correspondence from every region of the United States poured into the New Yorker’s office. A large number of readers expressed pity for the victims of the bombing. But an even greater number expressed deep fear about what the advent of nuclear war meant for the survival of the human race.

Of course, not all readers approved of Hersey’s report on the atomic bombing. Some reacted by canceling their subscriptions to the New Yorker. Others assailed the article as antipatriotic, Communist propaganda, designed to undermine the United States. Still others dismissed it as pro-Japanese propaganda or, as one reader remarked, written “in very bad taste.”

Some newspapers denounced it. The New York Daily News derided it as a stunt and “propaganda aimed at persuading us to stop making atom bombs . . . and to give our technical bomb secrets away . . . to Russia.” Not surprisingly, Henry Luce was infuriated that his former star journalist had achieved such an enormous success writing for a rival publication, and had Hersey’s portrait removed from Time Inc.’s gallery of honor.

Despite the criticism, “Hiroshima” continued to attract enormous attention in the mass media. The ABC Radio Network did a reading of the lengthy article over four nights, with no acting, no music, no special effects, and no commercials. “This chronicle of suffering and destruction,” it announced, was being “broadcast as a warning that what happened to the people of Hiroshima could next happen anywhere.” After the broadcasts, the network’s telephone switchboards were swamped by callers, and the program was judged to have received the highest rating of any public interest broadcast that had ever occurred. The BBC also broadcast an adaptation of “Hiroshima,” while some 500 U.S. radio stations reported on the article in the days following its release.

In the United States, the Alfred Knopf publishing house came out with the article in book form, which was quickly promoted by the Book-of-the-Month Club as “destined to be the most widely read book of our generation.” Ultimately, Hiroshima sold millions of copies in nations around the world. By the late fall of 1946, the rather modest and retiring Hersey, who had gone into hiding after the article’s publication to avoid interviews, was rated as one of the “Ten Outstanding Celebrities of 1946,” along with General Dwight Eisenhower and singer Bing Crosby.

For U.S. government officials, reasonably content with past public support for the atomic bombing and a nuclear-armed future, Hersey’s success in reaching the public with his disturbing account of nuclear war confronted them with a genuine challenge. For the most part, U.S. officials recognized that they had what Blume calls “a serious post-`Hiroshima’ image problem.”

Behind the scenes, James B. Conant, the top scientist in the Manhattan Project, joined President Truman in badgering Henry Stimson, the former U.S. Secretary of War, to produce a defense of the atomic bombing. Provided with an advance copy of the article, to be published in Harper’s, Conant told Stimson that it was just what was needed, for they could not have allowed “the propaganda against the use of the atomic bomb . . . to go unchecked.”

Although the New Yorker’s editors sought to arrange for publication of the book version of “Hiroshima” in the Soviet Union, this proved impossible. Instead, Soviet authorities banned the book in their nation. Pravda fiercely assailed Hersey, claiming that “Hiroshima” was nothing more than an American scare tactic, a fiction that “relishes the torments of six people after the explosion of the atomic bomb.” Another Soviet publication called Hersey an American spy who embodied his country’s militarism and had helped to inflict upon the world a “propaganda of aggression, strongly reminiscent of similar manifestations in Nazi Germany.”

Ironically, the Soviet attack upon Hersey didn’t make him any more acceptable to the U.S. government. In 1950, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover assigned FBI field agents to research, monitor, and interview Hersey, on whom the Bureau had already opened a file. During the FBI interview with Hersey, agents questioned him closely about his trip to Hiroshima.

Not surprisingly, U.S. occupation authorities did their best to ban the appearance of “Hiroshima” in Japan. Hersey’s six protagonists had to wait months before they could finally read the article, which was smuggled to them. In fact, some of Hersey’s characters were not aware that they had been included in the story or that the article had even been written until they received the contraband copies. MacArthur managed to block publication of the book in Japan for years until, after intervention by the Authors’ League of America, he finally relented. It appeared in April 1949, and immediately became a best-seller.

Hersey, still a young man at the time, lived on for decades thereafter, writing numerous books, mostly works of fiction, and teaching at Yale. He continued to be deeply concerned about the fate of a nuclear-armed world—proud of his part in stirring up resistance to nuclear war and, thereby, helping to prevent it.

The conclusion drawn by Blume in this book is much like Hersey’s. As she writes, “Graphically showing what nuclear warfare does to humans, `Hiroshima’ has played a major role in preventing nuclear war since the end of World War II.”

A secondary theme in the book is the role of a free press. Blume observes that “Hersey and his New Yorker editors created `Hiroshima’ in the belief that journalists must hold accountable those in power. They saw a free press as essential to the survival of democracy.” She does, too.

Overall, Blume’s book would provide the basis for a very inspiring movie, for at its core is something many Americans admire: action taken by a few people who triumph against all odds.

But the actual history is somewhat more complicated. Even before the publication of “Hiroshima,” a significant number of people were deeply disturbed by the atomic bombing of Japan. For some, especially pacifists, the bombing was a moral atrocity. An even larger group feared that the advent of nuclear weapons portended the destruction of the world. Traditional pacifist organizations, newly-formed atomic scientist groups, and a rapidly-growing world government movement launched a dramatic antinuclear campaign in the late 1940s around the slogan, “One World or None.” Curiously, this uprising against nuclear weapons is almost entirely absent from Blume’s book.

Even so, Blume has written a very illuminating, interesting, and important work—one that reminds us that daring, committed individuals can help to create a better world.

Lawrence Wittner (http://lawrenceswittner.com) is Professor of History Emeritus at SUNY/Albany.