KOREA: CHALLENGE AND RESPONSE

By René Wadlow

As the professor of economics Milton Friedman wrote “Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. When the crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, and to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes the politically inevitable.”

The current tension around the two Korean States, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and the Republic of Korea (ROK), is such a crisis. For the moment, it is not clear that Governments are willing to take the diplomatic measures necessary to reverse the tensions on the Korean Peninsula. Thus it is important that non-governmental voices be raised and that their proposals are taken seriously. Nongovernmental organizations can present policy choices that can help to resolve the multidimensional Korean security challenge.

Therefore, the Association of World Citizens (AWC) has proposed a two-track approach to the current Korean tensions. In a message to the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, AWC President René Wadlow stressed that a crisis can also be an opportunity for strong initiatives and action. The UN with historic responsibility for Korea should take the lead in organizing an UN-sponsored Korean Peace Settlement Conference, now that all the States which participated in the 1950-1953 Korean War are members of the UN. The UN-led Korean Peace Settlement Conference should be organized to lead to a North-east Asia Security and Nuclear-weapon Free Zone.

Such a Peace Settlement Conference is of concern not only to Governments but is one in which the voices of civil society are legitimate and should be heard.

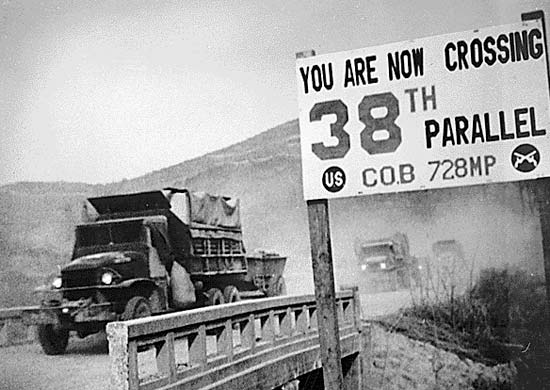

From 1950 to 1953 the first major international conflict to have taken place after the end of World War II saw the United Nations join the pro-Western South Korean military in its fight against the Communist North Korea. Neither side really won the war but since the 1953 armistice the Korean Peninsula has been divided in two along the horizontal border represented by the 38th Parallel.

In the past, there have been a series of dangerous but ultimately resolvable crises concerning the two Korean States. However, there are always dangers of miscalculations and unnecessary escalations of threats. Past crises have led to partial measures of threat reduction.

Partial measures of cooperation between the two Korean States, the Six-Party talks on nuclear issues and a number of Track II-civil society diplomatic efforts have shown the possibilities but also the limits of partial measures.

In the past decade, world attention has been focused on two Korean issues:

1) how to resolve the nuclear weapons-ballistic missiles issues;

2) how to help the DPRK to become food secure and to overcome a sharp inadequacy in food production. The food deficit points to broader structural obstacles, production and supply bottlenecks, and a generalized vulnerability of the economy.

Northeast Asia’s highly sensitive interlocking security issues are of great significance to the future of the region which includes China, Russia, Japan, the two Korean States and by extension the USA.

During the Cold War, Korea was to Asia what Germany was to Europe and Yemen to the Middle East – once a single people now divided along the ideological border of the rival blocs. Unlike Germany and Yemen, though, a quarter of the century after the Cold War has ended, Korea remains firmly divided. In the North, the world’s last Stalinist regime ruled by the Kim family continues to pose a serious threat to the pro-Western, democratic South Korea. (C) AP Photo/Korean Central News Agency via Korea News Service & Park Ji-Hwan/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Changing security perceptions and policies, unresolved conflicts and grievances, and concerns about nuclear and missiles proliferation are all elements that affect the stability of the region as a whole — and which also have global impacts.

In addition to the broadly based UN-led Korean Peace Settlement Conference, the AWC has stressed the need for regional cooperation and confidence-building measures which would improve the daily life of individuals and create the framework for greater future cooperation.

The AWC has highlighted that the Tumen River Development Project (TRADP), now often called the Greater Tuman Initiative (GTI), is probably the best framework for rapid cooperative development. The planning for a Tuman River economic zone at the mouth of the river had been drawn up in the early 1990s by the UN Development Program (UNDP – a vast free – economic zone which would involve parts of Mongolia, China, Russia and the two Korean States as well as Japan as a logical regional development partner. However, development has fallen far short of initial expectations for reasons both internal and external to the participating States.

As Milton Friedman pointed out, ideas can be dormant until a crisis occurs and then new steps must be taken. The AWC believes that the Tuman River economic zone is a real opportunity for cooperation among the States for the benefit of the people of the area.

Citizens of the World call for speedy and creative action to meet the challenge of Korean tensions with a response of cooperation and reconciliation.

Prof. René Wadlow is President of the Association of World Citizens.