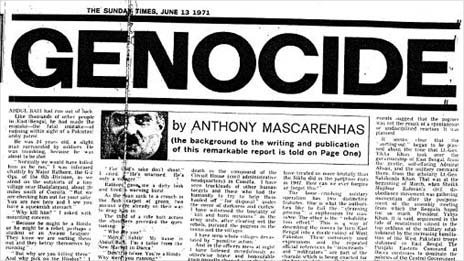

A L’OMBRE DU PAYS DES CEDRES, PAS DE REFUGE POUR LES SYRIENS

Par Bernard Henry

Lorsque l’on pense au Liban et à la Syrie, l’on ne peut oublier la longue guerre civile libanaise, l’ingérence permanente de Damas et la fin du conflit en 1990 qui laissa Hafez el-Assad, le Président syrien, seul maître du Liban. L’on se souvient de l’assassinat, le 14 février 2005 à Beyrouth, de l’ancien Premier Ministre libanais Rafic Hariri, élément déclencheur du retrait précipité du Liban de cette Syrie qui s’y croyait pour toujours en terrain conquis.

Rares sont ceux qui pensent, aujourd’hui, aux 1 200 000 Syriens réfugiés au Liban voisin, fuyant le conflit qui ravage leur pays depuis trois ans et la répression sanglante de toute résistance à la dictature de Bachar el-Assad, le fils d’Hafez. Ayant succédé en 2000 à son père décédé, le jeune Bachar avait tôt fait de décevoir les espoirs de réforme placés en lui, ayant tout au contraire accru l’écrasement de la dissidence à partir de 2004 et n’ayant laissé d’autre choix à son peuple, au printemps 2011, que de prendre les armes.

Ce n’est pas une actualité dominée par les conquêtes militaires de Daesh, le fameux « Etat islamique en Irak et au Levant », qui se veut même « Etat islamique » tout court maintenant qu’il a soumis une portion conséquente de l’Irak, qui va y changer quelque chose. Persécutant les minorités dans les zones tombées sous sa coupe, Chrétiens et Yazidis notamment, Daesh a réalisé l’exploit de concentrer sur ses méfaits l’attention d’une Session spéciale du Conseil des Droits de l’Homme de l’ONU le 1er septembre dernier.

Il n’en fallait guère plus à de bonnes consciences occidentales déjà enclines à soutenir Bachar al-Assad, certes jugé désagréable parce que dictateur, contre une révolution syrienne condamnée par contumace parce que contenant des éléments islamistes, pour parler aujourd’hui, en dépit même de faits accablant le régime de Damas, de blanchir Assad en tant qu’allié de circonstance contre l’islamisme barbare de Daesh, quitte à lui faire ainsi crédit de la création du groupe islamiste dont son régime est pourtant le premier fautif, à la manière d’un Frankenstein.

Mais que diraient ceux-là du sort des réfugiés syriens d’Ersal, ce village de trente mille âmes de la Beqaa à quelques cent vingt kilomètres au nord-est de Beyrouth ?

Un village libanais au cœur de la guerre en Syrie

Depuis le début de la guerre, bien que protégé en théorie par la frontière libanaise, Ersal est littéralement partie prenante au conflit syrien. La population locale ayant pris fait et cause depuis le départ pour l’Armée syrienne libre, Ersal accueille aujourd’hui non moins de cent dix mille réfugiés syriens, répartis dans plusieurs camps de la ville, dont par exemple celui d’Alsanabel.

L’été dernier, c’est la guerre proprement dite qui a fini par s’inviter à Ersal, avec l’incursion dans le village de combattants du groupe armé syrien Jahbat al-Nosra, avatar syrien d’Al-Qaïda, après l’arrestation de l’un de ses dirigeants, Imad Ahmad Joumaa.

D’interminables et violents combats ont ensuite opposé Jahbat al-Nosra et l’armée libanaise, avec, sous leurs feux croisés, des réfugiés syriens pris dans des affrontements par trop semblables à ceux auxquels, chez eux, ils avaient échappé. Même le retrait d’Ersal de Jahbat al-Nosra le 6 août dernier ne ramena pas la paix, l’armée libanaise se livrant depuis lors à une répression féroce à travers la ville et dans les camps de réfugiés – les réfugiés, dont treize mille sur les cent vingt-trois mille que comptait Ersal ont regagné la Syrie, leur lieu d’asile espéré étant devenu pire encore que l’enfer qu’ils avaient fui.

L’armée libanaise n’est pas celle d’Assad. Mais dans un Liban se cherchant désespérément un Président depuis mai dernier, elle est ce qui s’approche le plus d’une colonne vertébrale de l’Etat. Et bien sûr, sa mission première demeure la défense du territoire, mission dans laquelle un passé d’humiliation, non dans une moindre mesure pendant la guerre civile, lui interdit la moindre faiblesse.

Septembre porte le noir souvenir d’un épisode de cette guerre des plus humiliants pour l’armée libanaise – Sabra et Chatila, en 1982, lorsque plus de mille civils palestiniens et sud-libanais furent exécutés dans les deux camps de réfugiés beyrouthins par les Kataeb, les Phalanges chrétiennes d’extrême droite du Président Bechir Gemayel, sous le regard complice de l’armée d’invasion israélienne.

Cet été, Tsahal s’est à nouveau distinguée de manière macabre en se livrant à Gaza à son opération la plus meurtrière depuis la création de l’Etat d’Israël, rendant plus vivace et brûlante encore la mémoire de Sabra et Chatila.

Tant le présent que le passé privent l’armée libanaise de tout droit à l’indulgence face à une force armée étrangère sur son sol. Il n’en faut pas plus pour céder aux traumatismes du passé, quitte à voir Jahbat al-Nosra là où il n’est plus, à la manière des Kataeb obsédées par la présence de fedayin de l’OLP tapis dans l’ombre de Sabra et Chatila. Et Alsanabel en a fait les frais.

Des réfugiés bombardés délibérément, l’un d’entre eux torturé à mort

Le 25 septembre, sous le commandement du Général Chamel Roukoz, des blindés font feu sans sommation sur le camp de réfugiés, dont s’emparent aussitôt les flammes. Tout se consume, et bientôt, le camp entier n’est plus que ruines. Les militaires pénètrent dans un Alsanabel livré à la panique et arrêtent quatre cent cinquante réfugiés, les plaquant face contre terre aux pieds des soldats.

Le 25 septembre dernier, les blindés libanais attaquent le camp d’Alsanabel.

Les flammes ravagent le camp, réduisant les maigres biens des réfugiés syriens en cendres.

Les forces armées libanaises forcent les réfugiés d’Alsanabel à se coucher à leurs pieds, les dépouillant de la moindre dignité humaine.

Non, ce ne sont pas des sacs poubelle que l’on voit aux pieds des soldats libanais ; ce sont des réfugiés syriens, dont la vie et la dignité ne semble pourtant pas, aux yeux des militaires, valoir plus que cela.

Ce même jour à Alsanabel, les parents d’un jeune Syrien, Ahmad Mohammad Abdalla Aldorra, originaire de Qara, voient les soldats libanais leur apporter la dépouille mutilée de leur fils, arrêté le 20 septembre et qui a succombé à la torture.

Ahmad Mohammad Abdalla Aldorra, arrêté le 20 septembre par des soldats libanais.

Ses parents devaient ne le revoir que mort, son corps couvert de blessures reçues sous la torture.

Le sort des quatre cent cinquante personnes arrêtées demeure indéterminé.

D’aucuns peuvent bien s’obstiner à dire que, face au danger islamiste de Daesh, la dictature réputée « laïque » de Bachar el-Assad, même récusée par les capitales occidentales comme moindre mal face à une révolution syrienne jugée dévoyée par le djihadisme, peut constituer un rempart, pas idéal certes, mais un rempart.

Ce n’en est pas moins faire la scandaleuse économie, d’une part, de l’amnistie générale de cette année qui a ouvert grand les portes des prisons du régime pour en faire sortir, on ne peut plus sciemment venant de Damas, ceux qui sont allés aussitôt grossir les rangs de Daesh, et d’autre part, du verrouillage total de la société syrienne par le régime Assad depuis 2004, notamment au détriment des Kurdes qui, au sein de leur propre pays, sont devenus, plus encore que des étrangers, des invisibles.

Quant à la persécution de réfugiés syriens par une armée étrangère, en l’occurrence l’armée libanaise, contre quoi celle-ci peut-elle bien constituer un « rempart » ?

Une armée libanaise aux atours plus « laïcs » que Daesh est-elle plus fondée à harceler des civils, qui plus est des réfugiés ? Est-ce différent, a fortiori meilleur, que les attaques d’installations civiles et de lieux protégés, tels que des hôpitaux ou des écoles de l’ONU, reprochées à l’Etat d’Israël lors de sa campagne à Gaza l’été dernier ?

Un crime de guerre

Sabra et Chatila était un crime de guerre, Gaza cet été était un crime de guerre, et de la même façon, Alsanabel est un crime de guerre. Soit les autorités libanaises, cette fois seules en cause puisque c’est leur armée qui est intervenue et non une quelconque armée étrangère ou milice partisane, s’expliquent et/ou enquêtent de manière réelle et sérieuse, soit l’on saura quel parti elles ont désormais choisi – celui d’Assad et de Daesh, « les deux têtes du serpent » comme l’écrivaient le 18 septembre dernier dans Libération les Syriens Bassma Kodmani et Bicher Haj Ibrahim[i].

Ce serait dommage, et pour tout dire inexplicable, de la part d’un pays qui a tant souffert, dans son histoire récente, du fanatisme religieux et de la volonté de conquête militaire au mépris de l’intégrité territoriale d’un Etat et de l’unité de son peuple.

Ce que l’on reproche à Damas et Daesh tout à la fois, l’on ne peut l’admettre des soldats d’un pays qui accueille en connaissance de cause des réfugiés de Syrie. Le Liban a beau n’avoir pas ratifié la Convention des Nations Unies relative au Statut des Réfugiés de 1951, s’il accepte la présence de réfugiés étrangers sur son sol, il sait ce qu’il fait et, précisément, il le fait sous les auspices du Haut Commissariat des Nations Unies pour les Réfugiés, qui œuvre pour faire respecter cette convention.

Si en 1982, les Libanais, des Kataeb jusqu’aux communistes, avaient su mettre de côté leurs divisions partisanes après Sabra et Chatila au profit de l’intérêt national, alors l’on s’attendrait à ce qu’ils en tirent aujourd’hui l’enseignement au profit des réfugiés syriens présents sur leur sol, en commençant par ceux d’Alsanabel. A moins qu’ils ne le fassent, jamais le Liban, le « Pays des Cèdres », ne pourra offrir le moindre refuge digne de ce nom à ceux qui sont venus, dans un dernier espoir, l’y chercher de Syrie.

Bernard Henry est Officier des Relations Extérieures de l’Association of World Citizens.

[i] « L’Etat islamique et Assad, les deux têtes du serpent », Libération, 18 septembre 2013, www.liberation.fr/monde/2014/09/15/l-etat-islamique-et-assad-les-deux-tetes-du-serpent_1100773.

![Syrian demonstrators in Paris, France, vowing for "a democratic future" in Syria "without [Syrian President] Bashar [al-Assad] and without Daesh [ISIS]". (C) AWC/Bernard J. Henry](https://awcungeneva.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/without_daesh.jpg?w=604)