SOMALIA: SIGNS OF DANGER

By René Wadlow

Although Somalia is in a crucial geo-strategic position on the Horn of Africa facing the Arabian peninsula, the country had largely slipped from world attention except for African specialists. The government had disappeared in 1991, proving that people can live without a State if there are sub-State institutions of order and dispute settlement. Thus what order existed was the result of local warlords and clanic chiefs who provided order in very small areas, often only one town and a small area around it. In July 2006, a revitalized Islamic movement — the Union of Shari’a Courts — took control of the capital Mogadishu and in the months following extended its control to much of the country. There was a fear in other countries that Somalia could serve as a base for terrorist activities on the pattern of Afghanistan. On December 6, 2006, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1725 which authorized the creation of a regional African peacekeeping force to enter Somalia. The creation of such a multi-state force under the authority of the African Union seemed unlikely in the near term. The African Union forces are tied up in the Darfur, Sudan conflict. Therefore, Ethiopian troops moved in at the request, it is said, of the Transitional Federal Government. Ethiopia has the best trained and equipped army in the Horn of Africa. The Ethiopian forces quickly defeated the loose coalition of clanic militias which were supporting the Union of Shari’a Courts. On December 28, 2006, Ethiopian troops and representatives of the Transitional Federal Government moved into the capital Mogadishu. Thus an analysis of the background of the conflict in Somalia is merited as the conflict has potentially wider implications.

As William Zartman points out in his recent book Cowardly Lions “In a world scarred by State collapse and deadly conflict, external actors can no longer sit by and watch, mesmerized by the blood on their television screens. Nor can they hide behind the fear of their own casualties or long-term involvement as an excuse for inaction. External engagement is required when it is necessary to protect populations from their rulers and from each other. Such protective engagement is justified for its own sake, for humanitarian reasons, and for preventive security purposes, because these conflicts will continue to destabilize their regions and impose costlier involvement later on… The terrible fact is that in the major cases of state collapse in the post Cold-War era, specific actions identified and discussed at the time could have been taken that would have gone far to prevent the enormously costly catastrophes that eventually occurred… The reason why no action was taken also varies, ranging from loss of nerve to preoccupation elsewhere.” (1)

The UN General Assembly resolution on Somalia is an indication of a growing consciousness that international action must be taken early in a conflict before positions harden. The longer a conflict lasts, the more likely the parties will harden their positions to justify the costs in lives and money that has gone on before. With the entry of Ethiopian troops into Somalia in support of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG), the Somalia crisis seems to observers to be at a critical stage when the intensity of the conflict could escalate. Thus the need for action, although there is no clear view on what action should be taken. The first step to analyze the possibilities of action is to place the Somalia conflict into a historical and sociological framework so that alternative international actions stand out clearly.

An old map of Somalia as a colony of Britain and Italy.

In 1960, the Somali Republic was created by the union of a British colony and an Italian trusteeship area. The start of European involvement in Somali affairs began in 1902 when Italy, France, and Britain signed a Tripartite Convention that saw the Somalis divided between France taking Djibouti — a potentially important port and the terminal of the railroad to Ethiopia, the British which created Somaliland and also attached a separate area of Somali-speaking people to its Kenya colony, and Italy which created a separate colony of Italian Somaliland. The European powers recognized the expansion of the Ethiopian Empire under the leadership of Emperor Menelik which had taken control of the Ogaden area, inhabited largely by Somalis.

The British and Italian Somali colonies existed from 1902 until 1945. At the end of the Second World War, the Italian colony was placed under a UN administration as was all of Italy’s former African holdings. From 1945 to 1950, Somalia was governed by UN administrators. By 1950 Italy had regained international respectability and so Italian Somaliland was returned to Italy under a UN Trusteeship Council mandate.

1960 was a turning point for African independence. Although there was not among the Somalis a strong anti-colonial movement as there had been in North and West Africa, by 1960 both the French and the English believed that the colonial system as it had existed in Africa since the 1880s could no longer continue. There was a systematic granting of independence of the French colonies in 1960 and a drawn out granting of independence to the British colonies. Italy went along with the tide. Thus in 1960, both the UK and Italy granted independence to its Somali holdings and combined the two into the new state of the Somali Republic. However, there was a five day gap between the granting of independence to the UK colony and its integration into a united Somalia. This five-day status of independence now serves as the basis for the independence of the former British colony called again Somaliland, declared in 1991.

The once-united nation of Somalia now stands divided in three separate entities: Somalia proper, Puntland, and Somaliland.

By and large, the different colonial administrations had little impact on the lives of the Somali populations. The Somalis speak the same language and practice the same forms of Sunni Islam. The divisions among the Somalis are not tribal but clanic, with clans being followed by sub-clans, lineages, and extended families. Lineage is the most important identity. Thus one has frequent intra-clan tensions as well as inter-clan disputes. The sub-clan and lineage are the core social institutions providing personal identity, mutual support, access to local resources, and the framework of customary law, called xeer in Somali. It has been said that Somalis live in societies with rules but without rulers.

The pastoral clan organization in Somalia is a fragile system characterized at all levels by shifting allegiances, temporary coalitions and ephemeral alliances. Lineages usually exist for three generations at which time they split and form new lineages. In such a clanic, largely pastoral society, one does not need state institutions to function. Clans are not all equal; some are severely disadvantaged due to their social status and therefore had less access to water and grazing land. There are, however, some people who lived outside the Somali clanic system. There is a small minority on the frontier with Kenya who are agriculturalists and not Somalis. There are also a small number of urbanized Somalis, especially those living in the coastal cities who no longer followed clanic authority, as well as a small but growing educated bourgeoisie. (2)

The great majority of Somalis are Muslim. Somali Islam is largely Sufi based with three major Sufi orders: Qaadariya, Saalihiya and Ahmadiya with other smaller groups or followers of particular saintly figures. By and large, the Sufi orders have been non-political, but the best known of the anti-colonial Somali leaders was a member of the S aalihiya order. Sayed Mohammed Abdille Hasan, called by the English “the Mad Mullah” led a 20 year struggle against Ethiopia, Italy and England starting in 1899 against Ethiopia and ending with his death in 1920. He had been influenced by the earlier Madhi movement in Sudan.

Sufi Islam is largely non-legalistic, placing a large emphasis on the teachings and lives of local saintly persons. Somali Sufi orders have integrated into the customary law (xeer) certain elements of Shari’a law especially as concerns family law – divorce and inheritance.

During the last 25 years, and especially since 1991 with the end of state institutions, three other currents of Islam have been present and which are important in the analysis of the current political situation. Somalia is in the orbit of Wahhabist preaching sponsored by Saudi Arabia. This is a conservative, legalistic Islam, part of a wider Salafist movement. The Wahhabist school of thought has a good deal of Saudi money to open schools and medical clinics at a time when state facilities have largely disappeared. There is a reformist Islamic movement, Al Islah, which is heavily influenced by the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood and has some contacts within Pakistan. More important politically, there is a more radical At Itihad al Islamiya movement which is willing to use violence to further its aims. These non-Sufi movements are largely limited to larger towns and the few cities, but they have support from outside Somalia. (3)

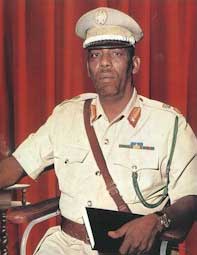

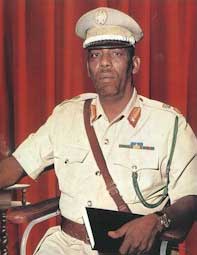

The first 10 years of independent Somali political life was largely a reflection of clan and sub-clan reality. The Parliament and the higher administration was structured on clanic reality. Government posts, seats in Parliament and government favors were distributed along clanic lines. The army was the only institution of the state that was not originally structured along clanic lines. Then in 1969, General Mohamed Siad Barre took control of the government. His ideology was an anti-clanic “scientific socialism” drawn from his limited reading of Soviet philosophy. However, he received support from the USSR, thus bringing Somalia into the Cold War. The Cold War helped to partition Africa into ideological spheres of influence. In order to counter Soviet influence in Somalia, the USA increased its support for conservative Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia.

General Mohamed Siad Barre, President of Somalia from 1969 to 1991 and the country's very last head of state.

Siad Barre, with the help of Soviet advisors, increased the size of the Army and the paramilitary forces. By 1982 there were some 120,000 men in the army with political commissars to develop ideological purity. Unlike the colonial period and the first years of independence during which the rural areas were left alone, Siad Barre extended government control to the rural areas, weakening clanic chiefs. Siad Barre also largely destroyed the independent bourgeoisies; some were jailed, more left the country to work elsewhere.

Siad Barre, followed by probably the majority of Somali leaders, had a pan-Somali ideology which maintained that those areas of Kenya and Ethiopia where Somalis live should be joined to Somalia. The ideology had already led in the mid-1960s to attacks on Kenya which were quickly pushed back and then a much bloodier 1977-1978 war with Ethiopia in an effort to annex the Ogaden area where most of Ethiopia’s Somalis live. The fighting in Ogaden brought heavy losses to both armies. While Ethiopia pushed back Somali troops, the losses have left deep scars in Ethiopia and a persistent fear of Somali policies.

At the time of the 1977-1978 Ogaden War with Ethiopia, there was a classic Cold War switch of alliances. A Marxist, Mengistu Haile Mariam, overthrew the emperor of Ethiopia and looked to the Soviet Union for help. In 1978, Siad Barre abrogated the USSR/Somali Treaty of Friendship and turned to the USA for help with weapons and training of the military. As Barre was uninterested in U. S. liberal-democratic ideology, he returned to governing on a clanic basis with members of his lineage, that of his mother and that of his principal son-in-law. His style of government under U. S. influence from 1978 until the end of 1991 ranged from autocratic to tyrannical.

With the end of the Cold War, neither the USA nor the USSR had much interest in supporting difficult and unpredictable allies. Thus by 1991 both Siad Barre and Mengistu had been forced from power by rebel movements. While Ethiopia, having a long history of a weak but centralized government, was able to re-establish a state structure, Somalia returned to a precolonial structure but with few of the conflict-resolution techniques of precolonial times. Thus, in addition to traditional clanic conflicts over water and livestock, there was a clash between traditional clanic leaders and army officers who had gotten a taste of power under Siad Barre and who now wanted to set up little militarized kingdoms over which to rule.

The 1960 merger of the Italian and British colonies had been more based on a desire of the Europeans to withdraw than any Somali urge to merge. The former British area reorganized itself after 1992 and took back the name of Somaliland. The Somaliland area is about the size of England with some 3,5 million people. In 1993, Somaliland reintroduced the structures of government: tax, customs, and banking. Somaliland has trade to Arabia and beyond through the busy port of Berbera and is helped by the remittances from the Somaliland disaspora of about one million in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States, in East Africa and some in Europe. Somaliland, the former British colony is calm and its administration largely unchanged in Hargeisa, its capital which has become a magnet for displaced middle-class Somalis. However, there is a deep fear among many African governments that if one African state breaks up, many could follow the same pattern. Thus no African government wants to recognize the independent existence of Somaliland, and Europeans and others will not go against the African consensus by recognizing Somaliland.

The flag of Somaliland as a would-be independent state.

Thus, it is in the former Italian area and its capital Mogadishu where fighting is taking place and where the dangers of increased conflict exists. The following analysis concerns only this former Italian Somali colony.

Siad Barre was in power from his coup in 1969 until January 1991. When he was forced from Mogadishu, he tried briefly to re-establish control but was finally forced into Kenya. He died in exile in Nigeria in 1995. Those who had forced Siad Barre from power were never able to reorganize central control of the country, nor even of the former Italian area. The country was divided into small fiefdoms headed sometimes by clan leaders but more often by military officers who had served in the government of General Siad Barre and had gotten a taste for power and the wealth which came within. These “warlords” as they were called carved out fiefdoms which served as a base for the exploitation of confiscated properties; plantations for banana export, the arms trade, and drug trafficking. Around the warlords are their business allies who run the plantations, make contacts with foreign companies for banana exports, and especially organize the arms and drug traffics.

The warlords used the clan and sub-clan organizations among ethnic Somalis to create alliances and build support. However, the warlords are not traditional clan leaders. There have always been conflicts among clans. However the violence in Somalia after 1991 was not caused by clan and sub-clan divisions but was a struggle for power among individuals. Once violence broke out, the clan and especially sub-clans provided a ready-made solidarity group, and old inter-clan disputes were reignited. (4)

Fighting continued over the control of areas between two fiefs. The result was economic and political chaos, with most people living a day-to-day existence. Many of the youth have been taken into the forces of the warlords but receive no education and even little military training. There are also independent bandit bands interested in looting.

Since governments do not like anarchy, there have been numerous efforts on the part of neighboring countries, in particular Kenya, to help the Somalis create a government. (5) After many failed efforts, there now exists a Transitional Federal Government (TFG) which is recognized by the African Union. The TFG is made up of some clan leaders, some warlords and some persons chosen from urban civil society. However, while people do not have much enthusiasm for a continuation of armed conflicts, there is little enthusiasm for the return of government either. Attitudes of animosity, suspicion, and hostility are dominant. It will have to be seen if the TFG is able to establish control over the country if the Ethiopian troops are withdrawn.

The Transitional Federal Government is, no doubt, more transitional than federal. Most international mediators have preferred to focus on trying to stabilise Somalia before addressing the Somaliland issue. The TFG has as president Abdullahi Yussuf — a war lord turned president — but its authority was limited to one large town, Baidoa, 200 miles from Mogadishu. Into the political void, Islamic groups that have always been around tried starting in June 2006 to take the high ground. The al-Ittihad al Islaami (Islamic Unity, often called just al-Ittihad) is a loosely structured group which has taken in a few floating Islamic fighters, many of whom had been been in Afghanistan or Pakistan. They see the similarities between the chaos in Somalia and the time after the departure of the Soviets from Afghanistan when the resistance forces were fighting for control among themselves. They hope that with a Taliban-like ideology of “Order and Islam will solve all your problems”, the people would help them come to power to put an end to the divisions among the warlords.

Most of these Islamist groups have created a loose structure called the Union of Shari’a Courts, sometimes called the Union of Islamic Courts. The current leader Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys is a former Army colonel as well as a former leader of the al-Ittihad though he claims that the Shari’a Courts have a broader base al-Ittihad. The Union of Shari’a Courts received funds but no troops from Saudi Arabian sources. The line between public and private funds in Saudi Arabia is never clear.

Ethiopia was the regional state most concerned by the rise of the Shari’a Courts and their potential control of the country. Ethiopia feared that the Shari’a Courts could revive the pan-Somali ideology as a way of rebuilding national unity and so might again try to join the Somali-populated Ogaden to Somalia. Since the 1977-1978 war, the Ogaden has taken on increased importance to Ethiopia. The area could have large quantities of gas but further exploration is needed to verify the amount and the possibilities to develop the field.

As Ethiopia is helping the TFG, the Eritrean government angry with Ethiopia for unresolved frontier issues and resentments from the long struggle for independence from Ethiopia has sent some troops to aid the Union of Shari’a courts. Thus the TFG, in the spirit of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” is trying to build links with the Eritrean Liberation Front, an armed insurgency against the Eritrean government.

Kenya also has direct interests in Somalia — Kenya’s northeast province is populated by ethnic Somalis. From 1963 to 1967 there was on-and-off fighting between Somalia and Kenya as part of the then “Greater Somalia” policy. There are also some 135,000 Somali refugees living in Kenya, some of them involved in an active arms trade.

Into these lands of intrigue, few want to adventure. Some countries, in particular the U. S. government, see the possibility of Somalia turning into a safe haven for al-Qaada networks. Sheikh Aweys of the Union of Shari’a Courts has already been designated as a terrorist by the USA for suspected links to al-Qaada. The USA has some 1,800 troops based nearby in Djibouti specializing in intelligence gathering and counter-terrorism. These U. S. troops are especially active since the 1998 attacks on U. S. embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam which had been prepared in Somalia. The USA is unlikely to get directly involved, but they sponsored the 6 December 2006 UN Security Council resolution which opens the door to African peacekeeping troops.

Once Ethiopian troops moved massively into Somalia in mid-December 2006, the fighting in Somalia was brought to the attention of the UN Security Council. The USA and the UK prevented a resolution calling on all foreign troops to leave the country from being presented. The delay in passing any resolution gave time to the Ethiopian troops to fight the forces of the Union of Shari’a Courts. In fact, the Courts had few foreign forces helping them. In a tightly structured clanic society as Somalia, foreigners, even Muslims, stand out and are not welcome. There is a real risk of betrayal of foreigners who can not be integrated into the protective network of a sub-clan. The Shari’a Courts were able to draw on the militias of some sub-clans, drawing upon clanic loyalties rather than on ideological conviction. The support of these sub-clans melted away once they saw the superior fighting force of the Ethiopian army. On December 28, Ethiopian troops and representatives of the TFG including Prime Minister Ali Muhamad Gedi and Vice Prime Minister Mohamed Hussein Aidid moved into Mogadishu with the top Shari’a Courts leaders going into exile in Yemen.

It is too early to know if the TFG will be able to consolidate its authority since it is a coalition of clans, warlords and former administrators who have little in common. It is also too soon to know what policy Ethiopia will follow. Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi has said that the troops will be withdrawn as soon as order is established. But who is to define “order”? It is important that those working for peace from outside Somalia follow developments closely. Somalia requires our constant concern.

References

1) I. William Zartman.Cowardly Lions: Missed Opportunities to Prevent Deadly Conflict and State Collapse (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2005)

2) I. Lewis. A Pastoral Democracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991)

3) I. Lewis. Saints and Somalis: popular Islam in a clan-based society (London: Haan, 1998)

4) I. Lewis. A Modern History of Somalia (Oxford: James Currey, 2002)

5) International Crisis Group. Negotiating a Blueprint for Peace in Somalia (Brussels: ICG, 2003)

Rene Wadlow is the editor of the online journal of world politics www.transnational-perspectives.org. He is also the Senior Vice President and Chief Representative to the United Nations Office at Geneva of the Association of World Citizens. Formerly, he was professor and Director of Research of the Graduate Institute of Development Studies, University of Geneva.